Author: Adam

-

The Adventures Of My Scoliosis In Japan

Sometime in 2003, Errol Linton – the leader of the band in which I played – had mentioned that we had a gig at the Park Tower Festival in Tokyo, Japan at the end of the year. I believed him a lot. But sure enough, in the Autumn we all had to troop down to the Japanese Embassy in Piccadily and get our visas. So far so good.

A couple of weeks before departure, I did my back in. I mean I really did my back in. I was having a shower and something went click and I doubled over in agony. I could barely climb out of the bathtub. I went upstairs on my hands and knees and phoned one of my students who was a fitness trainer.

“Get yourself to a chiropractor” he said.

“But I can hardly move!” I cried.

“Get yourself to a chiropractor or it will get worse,” he said with terrible certainty. So I looked up a chiropractor in the phone book (those were the days) and made an emergency appointment with a man in Paddington: Dr Ashton Vice – surely the most apt name for a chiropractor. Getting down the stairs, getting myself into a taxi – it all seemed to happen in very slow motion and every movement was blistering pain. But Ashton Vice was great. He sorted me out. A terse, abrupt South African, he x-rayed me and put me on one of his weird machines which sent electricity up my spine while he went off to look at the x-rays. He came back with a triumphant air.

“Look at this,” he said. “Would you build a house on that foundation?” He pointed to a kink at the base of my spine. “Congenital scoliosis,” he said with finality. “There was something wrong with your mum’s baking powder.”

Although I could see the humour, something in me railed at this.

“How dare you insult my mum’s baking powder!” I said. Ashton shrugged. It made horrible sense. My mother had always nagged at me for my dreadful posture, now I saw why. And it was all her fault! Fat lot of good this knowledge did me. “Why now?” I asked Dr Vice. He shrugged again.

“It could have happened at any time” he said. He gave me a bunch of exercises to do and prescribed me an industrial strength painkiller. I got myself home again, slowly realising that this whole business was going to bankrupt me. Visits to a chiropractor are not cheap. Neither are taxis. I was perennially broke as musicians are. I did the exercises, took the painkillers. They made me feel sick and sluggish. Horrible. The hell with this, I said to myself, I need some good strong weed. So I phoned a mate who I knew would be able to help me out (thank you, Paddy, eternally) and obtained a little bag of contraband. I still smoked tobacco in those days so I rolled myself a little joint and smoked it. I got absurdly stoned and forgot all about my back pain. I had my medicine.

At my next appointment with Dr Vice I told him what I had done. He laughed heartily.

“That’s exactly the right thing, but I’m not allowed to prescribe it.” I told him I had to go to Japan the following week, for work. He laughed again. “You’re not going anywhere.”

“But I HAVE to go!” I cried. “There are many people depending on it.” He looked at me hard and long.

“OK, mate. We’ll get you to Japan”

He told me not to sit down for too long otherwise I wouldn’t be able to get up again and he wrote a letter for me to hand to the airline staff, requesting an upgrade on medical grounds. (This proved hilarious. I showed it to the airline staff as I boarded. They took it very seriously. “Yes of course, Mr Blake. That will be £500 please.” I didn’t get my upgrade.) I had set out to Heathrow with my cheap Stratocaster in a soft case. No way was I going to fly my Gibson. I had mixed a generous dose of my medicine into a yogurt and ate it in the departure lounge. A couple of hours into the flight and nothing had happened. Damn, I didn’t put enough in, I thought. Then it kicked in. Oh boy… I wandered around the plane, grinning stupidly. I went in and out of First Class. They kicked me out. I went back. They kicked me out. It was quite a game. Next thing I knew I was standing in line at immigration at Tokyo airport, still stoned out of my gourd. “Are we in Japan yet?” I asked Errol and Jean-Pierre and Sam. “Shut up Adam” they said – not unreasonably.

We were met by the promoter, driven into the city, shown into a hotel. It was all happening in a dream. We each had our own rooms. Luxury. The loo seat washed your bum after you had used it. Weird. I did my exercises, kept the back pain at bay. We went out for dinner to a local restaurant. Of course, none of us could read Japanese and the restaurant staff didn’t speak English. We would stand up as waiters walked past with dishes and say: “That! Can we have that please?” We got along OK. We got fed. Across the street from the hotel was a service station and I lived for the next three days on rice and seaweed which was their equivalent of junk food. I bet it’s Americanised now. Anyway.

We were driven to the venue which was just round the corner and sound checked. Also on the bill for the two nights was the legendary Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown. Blues buffs will know him as a great man – guitar and violin virtuoso from Vinton, Louisiana. He was nearly 80 when we met him and he wore a big Stetson hat. He played with the absolute authority of a master. Jean-Pierre and I watched his set from the back of the hall on the first night. At one point, Jean-Pierre turned to me and said: “He invented this stuff.” Yep, he sure did. He was very friendly and on the second night he invited us all up for a jam – one by one. I got up there with my cheap Squier Strat and he motioned for me to take a solo. This I did. Don’t pinch me, I thought. I don’t want to wake up. I am jamming with Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown in Japan. It was all over very quickly and I fell back into the dressing room, completely overwhelmed. The festival was a tax loss for Wild Turkey bourbon and there was masses of it backstage. Anyone who knows me knows that I cannot really drink alcohol. I got absolutely paralytic on this stuff. You know when you get to that point when all you want is for the room to stop spinning and to go to bed? Well I got there in record time. Only trouble was, bed was in a hotel in Tokyo. All the street signs were in Japanese. It was night time. Somehow, and I really have no idea how, some homing instinct took over and I found my way back to my hotel room. The next morning I was told that by leaving so soon, I had missed out on a party/ jam session that had been a gas. What can I say? I’m a lightweight.

Also on this trip I visited the Buddhist Centre where I was treated like visiting royalty. They didn’t know I was coming, they just treat people well. “You want guidance?” I was asked. How could I refuse. I was shown into an office with an interpreter and a very old Japanese Buddhist lady. She must be dead now, bless her. She was awe-inspiring. Turned out she was very interested in mathematics and astronomy. We talked about how far prayer can travel through the universe. She told me that I must be specific with the Shoten Zenshin (protective gods). Tell them what I want and get to the point. Oh yes… I will always be grateful to her.

I can’t remember anything about the long journey home. Really nothing. I was completely done in. In a good way. I went to Japan with a bad back. Jammed with a blues legend, got drunk and received guidance for life.

And it’s all thanks to Errol. Nice one, mate. I owe you.

-

“Love’s Getting Nowhere”

A new version of an old song.

-

Prog Nightmare

You are a record collector of a certain age. You have a fondness for late 60s/ early 70s British prog. On holiday in a small seaside town you are browsing 2nd hand records in a junk shop when you come across a record that you have never seen before. You have never heard of the band or the album title. It has an elaborate gatefold sleeve, and it’s on ISLAND Records! Now you pride yourself on your near-encyclopeadic knowledge of the late 60s Island catalogue so this is something of a shock to say the least. You pull the record from the sleeve and, yes, it has a pink Island label. It would seem to be a 1st edition (perhaps the only edition) and it’s in mint condition. It has no price tag and you’re thinking it must be worth a fortune, whatever it is. You ask the shopkeeper. They are indifferent, busy with something else. “You can have it for a tenner”, they say, without looking. You slap a tenner down and all but run out of the shop. You’re on holiday. You don’t have a turntable with you so the record glints at you tantalisingly unplayable while you consult Wikipedia. Nothing. No mention of this band, this record, or any of the musicians listed on the sleeve. You look up the Island Catalogue No. It’s allocated to… withdrawn. Withdrawn. What? What IS this record? You can hardly wait for your holiday to end so you can get home and play this record. Your partner gets thoroughly irritated as you go through the motions of enjoying yourself. They hate this record already. “I wish you’d never set eyes on it!” As a goodwill gesture, you suggest going for a walk along the seafront. Peace reigns and small talk is made about where you will go for dinner. It is one of those perfect late summer English evenings. The seagulls are crying, the smell of fish’n’chips and seaweed. You almost forget the record. But as you both wander along you see a group of four young men, laughing and joking with each other, leapfrogging over bollards, amiably shoving each other the way young men do. Nothing remarkable about them except they all have long hair, scraggly beards. No hoodies or sports fatigues, instead they are wearing tight flared jeans, brushed denim, tye dyed. Instead of trainers, leather boots. As you walk past, you pick up the faint aroma of patchouli and underarms. Odd. They ignore you until you are almost out of sight. Then you notice they have all fallen silent and are looking at you from behind. You find a little restaurant that seems pleasant enough. You and your partner eat an unremarkable meal, pay your bill, leaving a tip that reflects that you are on holiday and are just about to leave when the four young men bundle in through the entrance, laughing and joking noisily as before. They spot you and immediately fall silent. One of them has a knowing smile. The others look uncomfortable. Odd. You smile nervously in their direction and leave without saying anything.

The remainder of the holiday passes without incident. The young men are not seen again. Finally, you’re back home. Partner gone out in a huff. “I’ll leave you alone with THE RECORD” said with no small measure of vindictiveness. You remove the record from the impeccable vintage sleeve, dust it (although it is in perfect condition), check for spindle marks again – although you know there are none. You put it on the turntable, lower the stylus onto Side 1. It’s great! Really good! Touches of Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Mott The Hoople, Free – all that that you would have expected, the period trappings of which you are so fond, but the songs are really good! Did Nick Drake hear this? You wonder. Did John Martyn? Could that be Richard Thompson guesting on lead guitar? He’s not listed in the credits. Sure sounds like him. It’s maddening! You can’t find out ANYTHING about this record – and it’s really good. Four songs on Side 1. Not too long, not too short, solos are beautiful models of taste and economy. Flip it over. Side 2 is even better!

Partner comes home before the end. “Its really good!” You say, beaming like an idiot. “I’m so pleased”. The sarcasm fills the room. You are alone with THE RECORD. What can you do?

The next day. You wake up after a fitful night’s sleep. The record has disappeared. Completely. You suspect your partner. They deny all knowledge. “What record?” They are convincing. They really don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. It has disappeared. It is as though it never existed…

-

Telepathy In Music

Dear Adam

I’m sure you are right about this but no research has been done as far as I know, and I can’t think how one could do it. Scientific methods are rather blunt and crude and not suited for something as evanescent and subtle as this. Do please tell us more

Rupert Sheldrake

———————————————————————-

Dear Rupert,

You have put your finger directly on the problem: if improvising musicians were aware that they were being scientifically tested for evidence of telepathic powers they would almost certainly be too self-conscious to provide any. However, some observations might be interesting.

The act of plucking music out of the air, spontaneous composition and performance, relies on the participating musicians having a great sense of intuitive sympathy with each other. There are many forms of this. The kind of improvisation I cited to your colleague was Bebop – the school of jazz pioneered by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie (amongst others) in the mid-1940s. Tragically, this coincided with a recording ban (to do with the United States war effort) so there is very little recorded evidence of what they achieved in the precise moments of their innovations. I have no idea how much, if any, technical knowledge of music you have, or if you have any interest in jazz, but I will plough on.

The great leap forward that they made relied on a hitherto unrealized thoroughness of knowledge of harmonic and rhythmic circumstances. They had a technical and theoretical facility that was right at the forefront of what was considered possible at the time. On an individual level, Parker seemed to find this came naturally (he was often described as a genius) whereas Gillespie had worked methodically and systematically to arrive at this point over the course of several years. When they met, they recognized immediately that they were working on similar lines and formed a musical partnership whereby they would play trumpet (Gillespie) and alto saxophone (Parker) in front of whatever rhythm sections they could find who were at all sympathetic to their ideas. Their musical revolution spread very quickly amongst musicians.

But what of telepathy? There were basically two frameworks they would use: the 12 bar blues and the 32 bar popular song form known as ‘Rhythm Changes’ (often known as “I Got Rhythm”). Whoever was leading the series of improvisations would convolute these frameworks to such an extent, and at such a speed, as to make it as difficult as possible for the other to anticipate or improve or complement it. This was part of the game: to one-up each other. But how did they do this? 1. Memory – of the frameworks involved, and of the results of previous “bouts” 2. Accumulated knowledge – of what gambits were available at any given moment in a constantly shifting landscape of possibilities. 3. Judgment – the wisdom, taste and experience to know what will work.

This makes it sound a bit like a boxing match but the goal was always music. To actually make music that was pleasing to the ear whilst systematically exhausting all possible permutations of the material. In a completely different context, J.S. Bach attempted something similar in his “Art Of Fugue” and “Musical Offering”. But to return to those three conditions, In my opinion it is the second – accumulated knowledge – that gives rise to telepathic activity. Parker KNEW that Gillespie had as thorough an understanding as he did, and vice versa, and that they were both of them at the cutting edge of uncharted musical territory, creating on their feet, precisely in the moment. A situation like this is very unusual and it created very unusual results. I wish I could point you at specific examples but, as I say, most of what they did went unrecorded. All of this conjecture I am engaging in is based on oral histories and scraps of unofficial recordings made by enthusiastic amateurs (e.g., Dean Benedetti) – also, on retroactive analysis based on studying recordings that DID get made (e.g. “The Famous Alto break”).

Essentially, jazz is a music that is founded on the ideal of telepathy. The idea that musicians will feel such empathy with each other that they will be able to produce beautiful music together more or less spontaneously. It depends, to some extent, whether or not you acknowledge intuitiveness as a form of telepathy. Certainly a jazz musician (once he has mastered the basics) will be judged by his peers on his intuitive skills. A highly skilled technician who “doesn’t listen” will never be as highly valued by other musicians as someone who maybe has less technical facility but a greater intuitive understanding of what is appropriate in a given or spontaneously improvised musical setting

There are, of course, other forms of musical improvisation. “Free Improv” has become quite a rarity nowadays but I recall seeing AMM perform on the South Bank. They dispensed with form altogether and often made sounds with “found objects”. The musical collective Henry Cow formed a sort of bridge between the extremism of AMM and more conventional forms of music making. This raises philosophical questions along the lines of “what is music?” which I don’t want to get into here. Although interesting, like a lot of philosophical questions, it is a massive digression. Let us just say that most people know what music sounds like and what it is for. Certainly small children do.

But one can’t run away from philosophy and it may be that that is the central problem: some things just cannot be quantified, measured, precisely understood and that is precisely why the scientific establishment are wary of, or downright hostile towards discussions on telepathy and why the music of such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie is not taught at music schools with the same vigour as Bach or Mozart (both of whom were, ironically, prodigious improvisers). I remember asking my teacher why the music of Terry Riley was not as “respected” in academic circles as that of Philip Glass or Steve Reich. “Because he’s an improviser”, replied my teacher. “The academics don’t know what to make of improvisation. It makes them nervous.”

Does this ring any bells with you?

I am sorry if I’ve waffled on without giving any precise examples. I have studied Indian Classical Music too, not in depth but enough to see that they have integrated improvisation into their formal pieces in a natural and unforced way that we in the West could learn a great deal from. We could also talk about the work of John Coltrane and Rashied Ali but it’s just more of the same, only more concentrated (it also excludes the casual listener in a way that a lot of Parker and Gillespie’s work did not.)

I do hope that this has been of some interest to you.

All the best

Adam Blake

-

Farewell Clem Burke

So sad to hear of the death of Clem Burke from cancer. He was such a lovely guy – a real gentleman of rock’n’roll.

I have a couple of Clem Burke stories. In the Spring of 1996 I did a little tour of Spain with a Los Angeles band named The Plimsouls. I was the only guitar tech and it was quite a demanding job. They had nine guitars between them, in all different tunings, and they liked them to be re-strung if possible after every gig. I would close my eyes at night and see the tuning meter. Anyway, Clem was drumming for this band and it took me at least three days to realise who he was. The penny finally dropped: Oh my God! You’re Clem Burke the drummer from Blondie. Clem smiled. I think he liked that I hadn’t known who he was and we became fast friends. We bonded over The Who and Jimmy Reed. Such things can form deep bonds. Especially on tour. Clem had the New York/ New Jersey attitude down to the nth degree. I’ve never seen anybody shrug with such effortless insouciance. Clem was on a strict macrobiotic diet at the time and therefore could not eat 95% of the food that was set in front of him. In Spain they had the severed legs of dead animals hanging over the counter in most of the cafes we frequented so he was basically fasting most of the time. This did not stop him from drumming like a Keith Moon crazed maniac on all the gigs. Nor did he ever once complain. When the tour ended we kept in touch for a little while. The Plimsouls disbanded due to real life getting in the way. Peter Case had a flourishing solo career. Eddie Munez had a good job as an illustrator. Blondie got back together. Clem went back to being an international rock star. But still he took the time to send me a handwritten note telling me of the band’s sad demise and when Blondie came to London he got in touch to invite me to the show at the Drury Lane Theatre. With my guest ticket was a backstage pass so I ‘went round’, as you do, and Clem was the genial host, introducing me to the singer who looked like the coolest auntie you never had, taking off her make up. She was lovely, but I didn’t stick around to make a nuisance of myself. “If you’re ever in LA, give me a call”, said Clem.

Well it so happened that I WAS in LA, a year or so later, visiting a dear friend. So I called the number Clem had given me. He picked up straight away and asked me for the address where I was staying. I gave it to him. “Give me 45 minutes,” he said. 45 minutes later he turned up in his beautiful rock’n’roll car and gave me a guided tour of his Los Angeles. We stopped at a juice bar on Santa Monica. He bought me a carrot juice. We clicked paper cups. “Welcome to Hollywood!” said Clem. We walked to the end of Santa Monica pier and I had my little American epiphany. Very poignant to consider now, with the unravelling of the America I loved. “I get it!” I said to myself. “I understand!” What the Americans get so protective about. The whole American THING revealed itself to me in a blinding rock’n’roll flash. All those Beach Boys songs suddenly made sense. I know it’s silly but it’s a very fond memory and Clem made that happen for me. It was him. I told him about it and he just smiled. What could he say?

We ended up in a diner. I offered to pay my whack but Clem wouldn’t hear of it. We said our goodbyes and I never really saw him again until a couple of years ago when my old friend Kevin Armstrong brought the ‘Lust For Life’ band to Glasgow. Trish and I went and had a great old time, dancing around to the rock’n’roll and I went backstage afterwards, looking forward to catching up with Clem. But I don’t think he remembered me and I didn’t want to press the case and besides, Kevin was being such a gracious host, introducing me and Trish to all sorts of people. It was a lovely evening. As I left Clem was sitting in an armchair looking tired.

Now he’s gone. Bloody cancer. Bless his rock’n’roll heart. Thank you, Clem. Wherever Keith Moon is playing, that’s where he’ll be.

-

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins – 15.8.1937 – 30.1.2015

It has been over ten years since Hoppy died of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s accompanied – as it so often is – by Lewy Body Dementia. It is a slow and cruel death. In Hoppy’s case, it took just over seven years to kill him. It involves the slow atrophying of the mental faculties. Hoppy regarded it as an observational project – “becoming stupid” – but it was a tragedy nonetheless as he had such a fine mind. I had the privilege of being his friend. In his last eighteen months or so, I acted as his secretary and PA. In his last weeks, I was one of his primary carers.

Up until his diagnosis in 2007, Hoppy worked in video – a medium he pioneered. He began in 1969 with some video equipment donated by John Lennon and Ringo Starr. He went on to found the Centre for Advanced TV Studies at his video editing facility, Fantasy Factory. As Joe Boyd pointed out in his obituary, Hoppy’s goal was always the democratisation of communication and, to this end, he wrote many articles in trade papers and organised many seminars for people who would otherwise not have had access to video equipment. He liked that video was cheap, whereas film was expensive. It was a matter of some regret to him that his work in video was so overshadowed by his work as a photographer but he took it philosophically. He was undoubtedly one of the best photographers of the 60s – as his book “From The Hip” attests. Many of the images are up online. He also worked as a part time botanist for the Royal Horticultural Society – a job he very much enjoyed. Hoppy was a kind man, an eternally open minded man. A brilliant scientist who took great pleasure in absurdity and in that which confounds science and, in this, he was a great teacher. He enjoyed life to the full. He danced, he played piano – he was particularly fond of Erroll Garner and Jimmy Yancey – and was always a snappy dresser, in the psychedelic stye. He loved women, and women loved him. Even in his last illness he had a beautiful young carer who brought him flowers and giggled whenever he smiled at her. He was stylish. Well into his 40s he would roller-skate around London. He had a classic English gift for understatement. In one of his last lucid intervals I said to him that he seemed to be experiencing several different realities simultaneously. “Yes”, he replied. “It’s most inconvenient.”

How did I meet him? Long story. I wrote it up in an open letter to Mike Lesser who was editor of International Times in 1978 and who was subsequently responsible for archiving International Times online.

In December 1977, aged 17, I had a fit of teenage rebelliousness and quit school, chucking in my ‘A’ levels to become a full time rock’n’roll musician. My parents were at war with each other at the time, going through a very unpleasant divorce, so although they were disappointed they didn’t really try to stop me.

In January 1978 I realised that I would have to get a job of some kind so, answering an advert in the Evening Standard I got a job as a telephone salesman, selling advertising space over the phone. A horrendous job that I could not have even countenanced had I had any idea what I was doing, which I didn’t. I was assigned to sell advertising space in the Port Of London Police Motor Club quarterly journal. A more obscure and irreIevent periodical it would be hard to envisage. I had to read a corny pitch script down the phone to car hire companies and try and convince them to blow their annual advertising budget on an advert that would do them virtually no good at all. After a couple of weeks of this I realised I had to quit but I thought I’d have a little fun with it before I did. I asked myself: who would be the least likely people to place an advert in such a journal? Answer: The Sex Pistols. So I called up their management office and pitched my idea to them. They thought it was a good idea but there was a snag: The Sex Pistols had broken up the night before in San Francisco. Thus I was one of the first people in the UK to learn of their sad demise. OK. So who would be the second least likely people to advertise in this thing? The counterculture newspaper: International Times (always knows as IT).

IT was functioning at the time and I had an up to date issue with a telephone number which I called. Editor Mike Lesser answered the phone. I explained my idea to him and he immediately said:

“Sure. We’ll do a swap ad.”

“What’s a swap ad?” I asked.

“You advertise with us, we advertise with you”, he patiently explained.

I expressed my doubts that this idea would be well received by my paymasters but I promised that I would put it to them and get back to him. This I did. They laughed at me and told me not to be so bloody silly. I relayed this sad news to Mike. I explained that I wanted to quit this nothing job and, on the spur of the moment, offered my services to him as a writer. He said “sure”, and invited me to the next editorial meeting. This was scheduled to take place the following week at an apartment in Notting Hill. I turned up to the meeting. As well as Mike Lesser, there were about six or seven people seated around a big table. In the middle of the table was a large brick of hashish. Mike introduced me to everyone present and I took a seat. As the meeting progressed, the brick of hash was dipped into repeatedly and within half an hour or so I was stoned out of my gourd. Somehow the conversation turned around to the idea of writing and publishing The Definitive History Of IT. Everyone looked at me.

“Why are you looking at me?” I asked.

“Because you’re perfect for the job!” Said Mike, amongst general agreement. “You’re young, you’re fresh, you have no personal vendettas, no scores to settle, you’re keen. You’re perfect.”

Gulp!

“But wouldn’t this be rather a big article?” I stammered.

“Article? This is a book, man!” replied Mike with great enthusiasm.

“But where do I start?” I asked in trepidation.

“You start”, said Mike with great emphasis, “with HOPPY.”

Everyone in the room nodded in agreement. You start with Hoppy.

What could I say? I accepted the assignment. Mike furnished me with Hoppy’s number and assured me that he was friendly and that he would warn him I was going to call.

So I called him: 405-6862. I can remember the number to this day. Hoppy answered the phone, yes, he was expecting my call. We made a date and I went round to conduct the interview – the first interview I ever did. I was nervous as hell when I rang the doorbell. Hoppy showed me into the living room at 42 Theobalds Road – commercial premises not designed for domestic arrangements. At that time, Hoppy had a silk parachute hung upside-down from the ceiling. I took in the ambience as well as this extraordinary man and it was love at first sight. I wanted this man to be my cosmic dad. (I loved my own dad very much but he was being a bit…difficult at the time.)

Hoppy wouldn’t let me record the interview. He insisted I take notes. He told me that I would remember it much better that way. He was right, of course. And he told me the whole story, of the foundation of the UK counterculture and the founding of IT. Chapter and verse. It was, maybe, the first time that he had really told the story. He had to tell it so many times later but at that time – early 1978 – it was still pretty much undocumented. It was an engaging story, to say the least. It still is. Hoppy chose to leave off his narrative around the time that BIT (the information and legal advice network) was formed and referred me on to Mick Farren. Farren was very friendly but he was stoned when I arrived to interview him, and he got me stoned and we ended up just talking about The Who and that, I am ashamed to say, was that. I was defeated by the hugeness of the task in hand and the daunting prospect of phoning up Farren and asking if we could do it again under more sober circumstances (I hadn’t yet grasped that a central feature of the counterculture was the ability to do anything whilst stoned.)

Getting back to Hoppy. I had mentioned that I was an aspiring musician and Hoppy, typically, immediately fished out a blank tape and told me to put some of my music on it and return it so that he could hear it. I was gobsmacked. He was really encouraging. So I did. When I brought the tape back, Hoppy wasn’t there but his partner Sue received me very genially. She assured me that Hoppy wouldn’t think I had ripped him off because I had taken a while to get the tape together. She got me stoned. There’s a surprise. Thus began my 37 year friendship with Hoppy and Sue. Over the years they came to many of my gigs and parties and suchlike. Hoppy would even sometimes take photographs which were invariably of the highest quality – even if he tended to dismiss them. He would give me little jobs from time to time, knowing I was broke. I occasionally worked in a small tape-op capacity for Fantasy Factory. It was strangely familiar, seeing as my family were all in the TV business. In 1988, Hoppy gave me a job sorting out his negatives which were in complete disarray. My gig was to put them in order and try and identify the subjects by holding the negs up to the light at an angle. I gradually realised that I was handling unpublished photographs of some of the most photographed people in the 60s. I said to Hoppy: “you know what you’ve got here?” He chuckled and said: “you tell me.”

Unpublished photographs of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones at their mid-60s peak for a start, I said! Hoppy was unimpressed. He was much more interested in the social history, the photographs of London as it had been, the photographic compositions. The pictures of pop stars were just gigs he had done for money, for Melody Maker etc. I explained that it was not so much about how good the photos were as who they were of. Hoppy had an instinctive distaste for this idea but eventually, after a great deal of cajoling, Hoppy suggested I gather together what I thought would be the most attractive shots to a photo gallery and he would make up a couple of contact sheets for me to punt on his behalf. Thus armed with some of the most iconic, and unseen, shots of “people dressed up as the 60s” as Hoppy used to call it, I made an appointment with a posh photo gallery in Notting Hill. I was received politely but kept waiting. A serious young man eventually emerged and I handed over the contact sheets. He got out his magnifying glass. It really was one of the most delicious moments, one to savour, knowing full well that I had something he very much wanted – although he didn’t know it yet. I watched as he tried to stay cool.

“You say these are unpublished?” he said, after a very pregnant pause.

“Yes.” I smiled.

“When can we meet this Mr Hopkins?”

We phoned Hoppy from the photo gallery’s office. He was in. I could hear the chuckle in his voice as an appointment was made – which I was invited to attend. For a few weeks there, I was Hoppy’s agent – and he paid me as one, with statements attached to notes saying things like: “this won’t buy many tins of beans”. At the meeting, Hoppy impressed the gallery like the visiting exotic that he was. A deal was struck and not long after, The Photographer’s Gallery in Notting Hill Gate presented Hoppy’s first fine art photography exhibition. The negs I had handled and identified were made into giant prints and sold for posh money. That was nice.

Of course, Hoppy had to get a proper agent after that and I was relieved that he did. A smart lady, Addie Vassi, who knew about photography and really appreciated Hoppy’s work. She got it. Eventually she went off to found her own gallery in Amsterdam but she always kept in touch and one of the first shows she put on at her new gallery was one of Hoppy’s pictures. By then, Hoppy had had many exhibitions and shows and his photos were appearing in many books – the latest being the cover of the most recent biography of William Burroughs. He eventually agreed to do a book, “From The Hip” – published by Damiani Editore. He gave me a copy when it was finally ready (he said he was 95% happy with the printing). It was inscribed: “Adam – it’s all your fault, innit? Hoppy”.

To say I miss him would be an understatement. I think about him every day. In this sense, ten years since his death seems so much longer – and also like no time at all. Hoppy would have loved to have been following the developments in quantum theory since his death. I suspect he probably is anyway, skating round the universe with a big psychedelic smile on his face. He was a one off. A natural leader, who totally opposed the idea of leaders. How lucky I was to know him. How empty the world is without him.

-

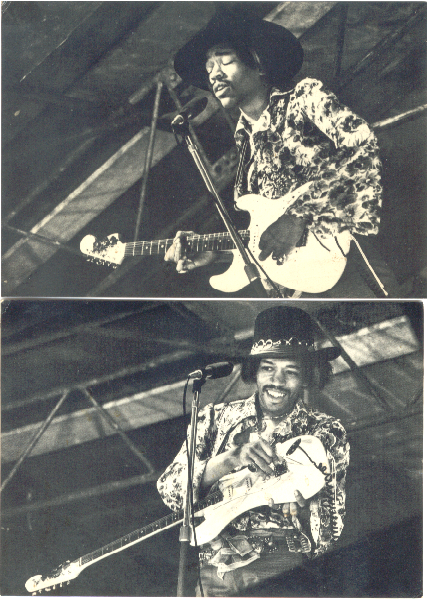

Jimi Hendrix’s Guitar Playing

Jimi Hendrix has been dead so long sometimes it’s hard to believe he was once alive and, almost certainly, playing the guitar. But his influence continues to be by far the biggest on guitar players – old and young and from beginners to advanced. I have made here a few general observations about his playing. Any factual errors I am grateful to have pointed out. The opinions are obviously my own.

The first and most important thing to note about Jimi Hendrix is that from the age of about 12 he played guitar as much as he possibly could. In his youth this would have taken the form of rigorous practice. He was self-taught so he would have worked out his own regimen, but it would have been impossible for him to have have attained the level of technical proficiency that he did without a great deal of work. Hard work is not necessarily something that most people associate with Hendrix. This is a mistake. Hendrix worked very hard indeed. Firstly by mastering the rudiments of guitar very quickly – probably by about the age of 15, secondly on the blues/r’n’b (’chitlin circuit’) package tours from 1962 to 65 and thirdly as a star in his own right. Recording, touring, interviews, promo – it’s astonishing that he found time to take all those drugs and have sex with all those women as well as developing such an extraordinary guitar style. Obviously, he was prepared to put the hours in.

The second most important thing about Hendrix’s guitar playing is its absolute fearlessness. He played at very high volume but this is not the same thing. His playing is always bold, prepared to take risks, always restlessly searching for new ways to play the old licks. In his later months (for his career as a successful composer and performer can be measured in months rather than years), one can imagine how frustrated he must have been at having to play material that no longer interested him, and his heroic and usually successful attempts to find new ways of playing it.

Hendrix’s guitar style did not appear out of nowhere. His time on the soul/r’nb package tours would have afforded him the opportunities to study many highly accomplished guitarists at first hand. Who knows? He probably sat in dressing rooms with the likes of Albert Collins, Ike Turner, Bobby Womack, Steve Cropper, Buddy Guy, Earl Hooker, Magic Sam, Curtis Mayfield. There’s no doubt that he was an exceptionally adept study. He absorbed all of the stylistic traits of these as well as listening closely to the recordings of Albert, Freddy and B B King, Otis Rush, as well as the usual Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Elmore James and John Lee Hooker. More unusually, he was also interested in the old pre-war country blues of the likes of Robert Johnson which he might have come across trawling the folkie dives of Greenwich Village in late ’65/early ’66 when he had more or less given up on making a career for himself on the soul/r’n’b circuit where had had served his apprenticeship. This is also where he encountered the music of Bob Dylan which had such an effect on his development as a singer/songwriter. It can’t be overstated how much Hendrix loved Dylan but this had little bearing on his guitar playing beyond, perhaps, underlining for him that occasionally it’s OK to just play simple tonic chords in root positions.

Much has been made of Hendrix’s fondness for 9th chords. Certainly he used the #9 chord a great deal. So much so that it is often referred to by musicians as ‘The Jimi Hendrix Chord’. The #9 chord is a very dramatic chord. It contains both the major and minor 3rd, creating what musicologists sometimes call ‘false relations’. Is it major or minor? Either way, Jimi used it a lot. It’s the signature sound of “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)”, “Purple Haze”, “Stone Free”, “Foxy Lady”. But Jimi liked the suspended 9th chord a lot too. He would construct melodies around strings of suspended 9ths (eg, the intro and outro to “Castles Made Of Sand”), and would insert them into the choruses of otherwise ‘heavy’ songs like “Fire” and “Foxy Lady”. He liked suspended 9ths on minor chords too (“Villa Nova Junction”). A thorough understanding of how to use 9ths is central to Hendrix’s style.

The bedrock of his guitar playing is, of course, the blues – at which he was an absolute master. As a straight Chicago style blues soloist he was at least the equal of any of his contemporaries (Magic Sam or Buddy Guy, for example) and streets ahead of such as Eric Clapton or Mike Bloomfield. His ability to use the blues scale in the most exquisitely expressive way – his control of bends, dynamics, his use of space (eg, the Albert Hall take of Elmore James’s “Bleeding Heart”), all mark him out as by far the most impressive blues player of his generation. But blues was just one of the styles he played. He also knew jazz and soul, and he also created his own uniquely mutated blend of psychedelia. The late Ian MacDonald and the very much alive Charles Shaar Murray have pointed out that the songs Hendrix wrote when he first came to London in Autumn ’66 are as much in thrall to The Beatles “Tomorrow Never Knows” or The Who and The Yardbirds experiments with feedback as they are to the black American musical traditions that Hendrix had grown up with. From the guitar playing point of view this leads us to the other most important element of Hendrix’s style: His use of the guitar as a sonic sound source. He would use everything at his disposal to create new aleatoric musical sounds. Obviously a lot of this was achieved with effects pedals: wah-wah, fuzz, phasers, dopplatone etc – very primitive by today’s standards but absolutely up to the minute for the late 60s. In the studio he would spend hours playing with backwards tapes, stereo echo, flanging etc. But strictly from the guitar end, Hendrix used every possible sonic possibility the Fender Stratocaster could offer. Interestingly, he never (to my knowledge) experimented with open tunings and he only ever used slide in the most casual way (a beer can, a lighter, a knife) but the slide solo on “All Along The Watchtower” remains a miraculous achievement. I have never heard anyone able to replicate it. He would routinely remove the plate at the back of the guitar that housed the springs for the tremolo unit and use these springs in his music. He was an unsurpassed master at the use of the tremolo arm and would also use the pick up switch to create rhythmic asides (eg. “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)”). This side of his music is well represented on “3rd Stone From The Sun”, “EXP”, “And The Gods Made Love” – all of them quite unique in their way and quite extraordinary in the context of music that was ostensibly described as ‘pop’.

Hendrix liked to dabble with jazz. His use of a perfectly executed tritone substitution at the end of the 2nd chorus of “Villanova Junction” at Woodstock demonstrates that he was conversant with jazz harmony (whilst gesticulating to the rhythm section what the hell was going on) but one senses that he was wary of jazz – of getting in too deep. In interviews he was sometimes quite scathing about people playing endless choruses of “How High The Moon” and showing off for each other so it’s possible he had some bad experiences in his early career. Nevertheless, the whole of Miles Davis’s ‘electric’ phase (from “Bitches Brew” and “In A Silent Way” through to “Pangea”) is unimaginable without Hendrix’s influence, likewise therefore the whole Mahavishnu/ Return To Forever thing over which we will draw a discreet veil for present purposes.

Hendrix played loud electric guitar and, apart from one absolutely gorgeous exception (“Hear My Train A-Comin’”), never played acoustic. But at even the highest volume, he played with great care and attention (unless he was upset or angry, which did happen sometimes). He would routinely turn the amplifiers up full and used the volume control on the guitar for all his wide dynamic interplay. His dynamic range was absolutely enormous, possibly still the widest of any electric guitarist. The delicacy of “Little Wing” or “The Wind Cries Mary” – interpolating those beautiful Curtis Mayfield double stops combined with his own little melodies in 4ths and suspended 2nds, so hard to finger and even harder to make them sound just right – these could give way at a moment’s notice to simply the biggest guitar sound ever heard (it still astonishes me to think that “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)” is just ONE GUITAR.)

I think that’ll do for now. If I think of anything else, I’ll add it.

Bottom line: You want to play like Jimi Hendrix? PRACTICE!

-

Camembert Electrique

Once upon a time Richard Branson wasn’t a bad joke but the proprietor of a few record shops and a maverick indie record label. He was never particularly interested in music but he was savvy enough to employ people who were. After catching one of the luckiest breaks in the history of the music business with Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” – who could have guessed that hundreds of thousands of people would want to buy 50 minutes of hippie muzak? – Branson’s A&R department assembled a roster of uniquely interesting artists. Very much like Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, Virgin Records in the early to mid 70s was a trademark of quality. If it was on Virgin you might not like it but it almost certainly wasn’t boring. In 1973, Virgin put out “The Faust Tapes” for the price of a single – 49p. Like thousands of others, I was intrigued by the Bridget Riley cover (“Crest”) and enticed by the low price. I would have been nearly 13 years old. I bought it and took it home and played it on my long suffering parents teak stereogram. Well… The Beatles “White Album” was the second album I ever owned and I was one of those Beatle fans who actually liked “Revolution No 9”. “The Faust Tapes” seemed like a whole album of “Revolution No 9” with bittersweet musical interludes ranging from delicate acoustic guitar set to poetry in French and German to hard rocking saxophone and electric guitar bashing. I liked it. It was ear opening stuff. Thanks Richard. Nice one.

The following year Virgin put out “Camembert Electrique” by Gong, again for the price of a single which by now had gone up to 59p. I knew nothing about Gong but the cover looked interesting and, after my Faust experience, I was happy to take a punt on it. Once again, I liked it. In places it was as wacky as Faust but it was coming from a more recognisable place. Or so I thought. There were electric guitars and drums and bass. Some of the tracks seemed to be actual songs. You know. It sounded a bit like rock music, or thereabouts. I loved the “space whisper” of Gilly Smyth. “I am not free… I am not free…” It got right inside my head. It didn’t sound like anything else. Once again, thanks Richard. (Oh I know, it was probably Simon Draper, but Branson paid for it.)

In the Punk purges of ’77 and ’78, like a lot of pretentious posers of my generation, I got rid of large chunks of my record collection in case I was seen in possession of a Deep Purple or (worse) a Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow album. A lot of deadwood was disposed of but also a lot of babies were thrown out with the bathwater. I had to buy back all my Free albums over the next twenty years, for example. That’s fashion. But funnily enough, “Camembert Electrique” never got culled. It would sit there, in my collection, unplayed but strangely immune to purges, for year upon year. I remembered that I liked it and that was enough.

So the other day, for no particular reason, I played it. How does it stand up? Strange record. What is the vocabulary of this music? Does anyone care any more? In the intervening 45 years or so I had learned all the back story: Gong were formed in France by Australian Daevid Allen who had been forced to leave Soft Machine when he was refused re-entry into Britain after having overstayed his visa. Allen and his wife Gilly Smyth were old style/ new style bohemians, propagandists for what became the hippie lifestyle. Allen wasn’t much of a musician but he was an effective bandleader and he had a vision. He had the talent for drawing musicians in – excellent players like Didier Malherbe and Steve Hillage – and bending them to his will. Later on, he would develop that irritating twang that suggested that if only everyone were as hip and knowledgeable as he, then how much better the world would be (Roy Harper and Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson are also guilty in this regard). But “Camembert Electrique” doesn’t suffer from that insufferable Flying Teapot/ Pothead Pixie mythology that would overwhelm Gong albums until they sounded like membership cards for an idiot club. Instead, you get a bit of tape collage, a bit of random dialogue, leading into a six minute song called “You Can’t Kill Me” made up of whole tone scale riffs and odd time changes and lyrics full of angry paranoia. It’s quite full on. Gong weren’t at this time possessed of the chops to play the jazz/rock fusion that would bore them and their audience into somnambulent submission at the end of the 70s. Here they trundle along, pulling these angular riffs behind them with all their strength. It ends abruptly and then begins… a joke track. A silly mock-portentous song in praise of being stoned. Well, is it really so much more risible than “Drinking Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee”? A lot less danceable certainly. But these two tracks set the tone. Allen really liked the whole tone scale. It provides the basis for a lot of this music. But the whole tone scale doesn’t really go anywhere (except, perhaps, to the nut house) and it’s when you get a bit of relief, as in the gentle melody of “And You Tried So Hard”, that the album’s enduring likability returns into focus. In 1971, when the album was recorded, Gong were unequivocally a hippie band. They lived communally and no doubt took industrial quantities of psychedelic drugs. Out of this came music which was unique to them. Those who love it love it fiercely. Gong never sold out but they changed, inevitably they became more professional and eventually the musos took over and Allen found himself cutting out of his own band. Some people like the jazz/fusion Gong. I’m not one of them. I don’t even much like jazz/fusion when it’s done properly. But I find I still like “Camembert Electrique”. Its a brave little record, a friendly record but with teeth – when Gilly Smyth intones “I Am Your Animal” she’s not messing about. There’s nothing else like it and anyone who is interested in what happened to that little corner of the psychedelic past should find it, or dig it out, and dust it down and listen to it.

-

Amazing Grace

I first became aware of “Amazing Grace” when Judy Collins had a hit with an acapella version in about 1971. I knew nothing about the song but I thought it was beautiful. I thought Judy Collins was beautiful too. I picked up the 45 as a cut-out for 30p. I daresay my mother was a bit surprised to hear a Christian hymn coming out of my bedroom as a change from T.Rex and The Beatles but she didn’t say anything.

Then it cropped up on Rod Stewart’s “Every Picture Tells A Story” album which I bought with my 12th birthday money. It was unexpected as it was uncredited on the sleeve. Rod sings it beautifully, to Ronnie Wood’s acoustic slide guitar. Thus it became part of my DNA as I played that album into the ground (as I’m sure did everyone who bought it).

Some years later, I had discovered the joys of the country blues and I heard Mississippi Fred McDowell doing it. I began to realise that there was a small sub-genre of the blues that was not Gospel but was religious (Christian) in subject matter. Sanctified blues. Lightnin’ Hopkins, taking a break from singing about women and gambling, would sing: “Jesus won’t you come by here, now is a needy time…” and it would stop me dead in my tracks every time. Blind Willie Johnson, the greatest slide guitar player ever recorded, dedicated every note he ever played to God – and lived a life and died a death so cruel it could have come straight from the Old Testament.

Fast forward many years and I was busking as usual when a nurse came by and asked me if I would be interested in playing for the local old folks home. There was no money but I was promised NHS coffee and as many biscuits as I could eat. So I said yes and we fixed up a time. I arrived, and just before I went in to play the nurse told me that all the people I was to be playing to had advanced Alzheimers. OK…

I started playing. They completely ignored me. I thought I should try and play something they might know. So I played “Amazing Grace”. Every one of them started singing along. The whole room was full of people in their 80s and 90s who had lost their marbles but could sing the first verse of “Amazing Grace”. And me. After awhile I stopped and tried to play something else. No. They carried on singing “Amazing Grace” and several of them started dancing and swaying about. The nurses were chuckling. I was chuckling. We had quite a time of it. I told this story to a Christian couple I know (they know who they are) and said it was “cool”.

“Yeah”, they laughed, “the Holy Spirit is cool”.

Most of my friends know I’ve been practicing Buddhism for 30 years or so but I feel that someone ought to play sanctified blues, even if it’s only me, and so I like to get up on a Sunday morning, if I’m able, put a suit on and go out and play a few sanctified melodies. Not too loud. I feel it would be hypocritical of me to sing them – but I sing a few words here and there, just to move the tune along. Today was interesting. I played “Amazing Grace” and a man stopped in front of me. He looked like a devil. He had very loud and expensive clothes and a dangerous look in his eye. He interrupted my playing.

“What’s that?” he demanded.

“Amazing Grace”, I replied.

“No. That.” he said, pointing at my CD on my guitar case. “How much?”

“Eight quid”, I said.

“Will you do it for a fiver?”

“Do you have to knock me down?” I asked.

“Yes”, he said, pulling out a £20 note.

“I haven’t got change”, I said.

“I’ll get change”, he said. Five minutes later he returned with ten 50p coins. He handed them to me. I handed him a CD. “I like your music”, he said. Then he was gone.

After that, I carried on playing. The music came out almost without my thinking about it. It sounded exactly right. I’ve rarely had such an enchanted sound as I had today. As I felt pleased with myself I thought about how one must put one’s ego at the service of the music, instead of putting the music at the service of one’s ego, and about how difficult this is. About how the greatest musicians are essentially vessels through which music passes. Not with all music of course, but with certain kinds – like Blind Willie Johnson or J.S.Bach or Vilayat Khan. The high mountains of music where the air is clean but not that many people travel. This sounds incredibly pompous but in actual fact demands absolute humility. As I was thinking about all this, I was earning money. Or money was appearing. I couldn’t decide. So many things to think about. An Irishman waited patiently until I took a break. He introduced himself and asked if I gave lessons. I told him that I did and I gave him my card. He gave me a fifty pound note. Nobody has ever done that before in nine years of busking. “Put that on account”, he said, and went off to buy me a coffee.It seemed I could see the condition of every soul who walked past me. I am not claiming for myself any special insight. Merely remarking that what is usually obscure to me seemed clear today. The children danced. The dogs barked. The Italian tourists ignored me. An Israeli lady stared at me for many minutes. We talked awhile. A Frenchman complimented my playing. The rain started. Then stopped. I will be gone from here soon. I will miss mornings like this.

-

“You Are Beautiful And You Are Alone”

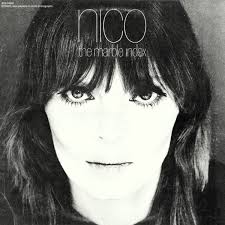

I finished the Nico biography. It’s surely a good thing that the author – Jennifer Otter Bickerdike – is so keen to rescue Nico from being viewed purely from the perspective of the famous men with whom she had affairs. Why then does she quote virtually word for word from a particularly pornographic memoir by an ex member of The Doors on Nico’s fellatio technique? Could it be that her editor at Faber advised her that a certain amount of lurid sex sells books? Talk about disingenuous. This is just the most egregious example. Elsewhere we have talk of how she apparently preferred taking it from behind and how her last manager ached to oblige her in this regard. Right…

In other respects, the biography is fairly standard. Bickerdike is to be congratulated for tracking down virtually everyone who ever had anything to do with her subject and for quoting from just about every interview she ever gave. Her writing style can be irritating. So many times she refers to Nico as “the blonde singer”, “the German chanteuse”, or just “the German”. Surely this is elementary tabloid journalism, unworthy of someone who brandishes her PhD in ‘Pop Culture’ in the first paragraph of the first chapter. Nevertheless, what emerges is a portrait of a person fatally damaged by her childhood growing up in the ruins of post-WW2 Germany. Stepping over rotting human corpses, stumbling through rubble, with no security at home or in her family – Christa Paffgen’s transformation into Nico the model, the singer, the Warhol Superstar, the film maker and eventually the helpless heroin addict is charted logically and with no small amount of sympathy. All of this is fine but what I cannot understand is why Bickerdike so studiously avoids making any attempt to discuss Nico’s actual music. Anyone who has paid any attention knows that “The Marble Index” and “Desertshore” in particular are extraordinary musical creations, quite unique and uncompromising visions of European Gothic high Romanticism. A glaring exception to Bickerdikes exhaustive index of quotes is Lester Bangs’s 1978 essay on “The Marble Index” which is, to my knowledge, the only serious critical attempt at understanding Nico’s vision. Surely this is more noteworthy than her list of lovers? I cannot believe that Bickerdike is unaware of this essay. Perhaps she is jealous that a grungy man could have had more perspicacity on her subject’s muse than she does (she is obviously deeply in love with Nico).

Anyway. I’m glad I read it but I won’t be referring to it often. For the record, James Young’s “Songs They Never Play On The Radio” remains by far the best book on Nico, whose unflinching music remains as elusive and timeless as it ever was.

-

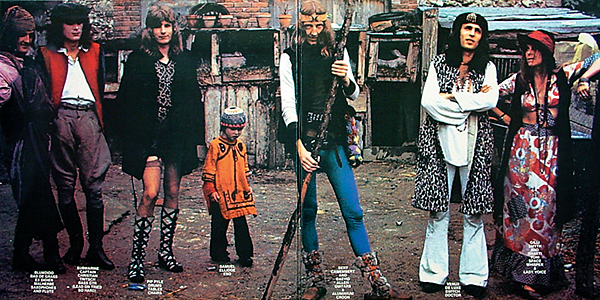

In Search Of Hawkwind

So in a fit of nostalgia for my old Ladbroke Grove stomping ground I spent rather more money than I anticipated picking up a first edition copy of Hawkwind’s “In Search Of Space” – complete with ‘flight log’ (this item being what made it more expensive as, in almost every 2nd hand copy that turns up, the ‘flight log’ is missing). Now over half a century old, this cultural artefact has such a strong flavour of its particular time and space and atmosphere, I figured it was time to give Hawkwind a reassessment. The cover is an elaborate visual production: a die cut fold out with photographs and lyrics and credits, an enigmatic aphorism on the back (“Technicians of spaceship Earth. This is your captain speaking. Your captain is dead”). The 24 page illustrated ‘flight log’ contains a multitude of pictures – space scenes, Stonehenge etc – and consists of the various ramblings of poet and author Robert Calvert on such subjects as time and space travel and the dormant period of cattle ticks – presented in the typeface favoured by International Times, the Underground newspaper. It is a curiously ornate and wordy document. I can imagine that few people read it all the way through. However, it is never less than thought provoking and at no time does it patronise its potential audience. It is an authentic piece of psychedelic sc-fi gobbledygook and, as such, deserves to be revisited and enjoyed.

So what of the music? On one level, to anyone even remotely familiar with the psychedelic music of the late 60s and early 70s it could be described as generic. In other words, it’s a bunch of stoned freaks making a racket. While this is undoubtedly true, what interests me at this distance is what this racket actually consists of. What are the rhythms? The note choices? Where does it come from, this music? Side One throws us in at the deep end with a 16 minute THING titled “You Shouldn’t Do That”. It sets up a very percussive and anxious groove and soon enough admonitory voices are reciting the title over and over. You shouldn’t do that because they “cut your hair, you get no air, you’re getting aware…” The sound is very processed. Primitive synthesisers make swooshing noises (Hawkwind’s signature sound), the saxophone plays through a wah-wah pedal, the bass acts as drone and pulse, the drums are strangely undermixed, the guitars churn through fuzz and wah. Every so often the whole ensemble comes together to play a militaristic staccato riff. The atmosphere is paranoid and foreboding. The rhythm goes in and out of phase which acts as an audio trompe l’oeil, so the listener is not sure where the ‘one’ has gone. But by this time, if the music has been loud enough and there has existed enough room, the listener has danced themselves into a kind of whirling dervish state, certainly too far gone to notice where the rhythms have shifted. This music is community music. It has a function and it exists to provide a soundtrack to a lifestyle.

Mick Farren once opined that it was rather a shame that Pink Floyd became the house band of the UK counterculture as their music was so cold and alienating. Syd Barrett may have twinkled very brightly for a very short time but even he was pre-occupied with space – the jolly madness of “Bike” notwithstanding. The first track on the first Pink Floyd album is “Astronomy Domine” and their theme tune (and therefore the theme tune of the nascent UK underground) was “Interstellar Overdrive”. The idea of space exploration must have been incredibly exciting in the late 60s, before the moon landing. Obviously a great many devotees were exploring inner space via psychedelic drugs so exploring outer space was the obvious corollary. Four years later, in 1971 when “In Search Of Space” came out, the audience for this kind of exploration had coalesced into a hardcore. The fashion followers had long since abandoned hippie as a look, weekend hippies had abandoned the ideals of the movement and returned to the open arms of capitalism, the teenage runaways who could go home to their parents had done so and many of the rest had cut their hair and got ‘proper jobs’, leaving their hippie dabbling behind and hoping there weren’t too many photographs. Those left were the true believers, those who had nowhere else to go, the anarchists, the full time squatters, the hippie proletariat who had burned all their boats in the ‘straight’ world and who habitually faced persecution from the police and complete non-comprehension and hostility from the general public. They scattered all over the UK in little pockets here and there but in London they centred around Ladbroke Grove. And Hawkwind lived there too, with them, right in the thick of it. Accessible and available, a people’s band – to a certain kind of people. They were not alone. Quintessence shared the audience and the location but where they had God, Hawkwind had space. Quintessence’s music is light and airy, full of good intentions and holy offerings, Hawkwind’s music is oppressive, dark, possessed of a grim determination to look The Void right in the black hole. It also contains a strange solipsism: “I am the master of this universe, the winds of time are blowing through me”. If space is infinite and we are infinitesimal, then perhaps the reverse is true? “We Took The Wrong Step Years Ago” as a title sums up the mood rather well. The rhythms are mostly four square on a robotic pulse but with enough syncopation to be danceable. There is no showing off in this music, no virtuosity, no flashy solos – which is interesting given that the early 70s were a time for flashy show off solos. It seems the music exists to serves the aspirations of its audience – to get as far out as possible in every sense.

I see and sense all this now but I rather looked down my nose at Hawkwind in my youth. I enjoyed “Silver Machine” when it was a hit but I never took it seriously. It was too lumpen, too plodding. Even then, I liked my rock’n’roll to swing and “Silver Machine” didn’t swing so much as lurch. Even so, I picked up an ex-juke box copy for 20p or so and found that I enjoyed the ‘B’ side more. “Seven By Seven” featured an immaculately enunciated recitation by Robert Calvert from which I learned the word ‘fortuitous’. It also had a comically dramatic guitar solo that went up and down the scale of A minor and which I figured out how to play on my cheap Les Paul copy. My friend Graham at school got the bug and started buying their albums. Up till then he’d been my source of Bowie and general Glam so this was quite a departure. He bought “Space Ritual” on cassette and we’d listen to it on our tiny mono battery operated cassette players. To me it all sounded the same, like a psychedelic washing machine, but he would go glassy eyed and talk about science fiction. He would put imaginary space landscapes cut out of sci-fi mags on the wall next to his pictures of Bowie and make me mix tapes of this stuff. (I should mention that Graham was very poor and earned all the money for this himself by working crappy jobs after school and at weekends.) He was my mate. I used to regale him with Yes and Curved Air and Caravan so we were about even. After I had got good enough on acoustic guitar to play through a few songs from start to finish, he and I would try our luck busking on Portobello Road. Graham would play cheap bongos and sit cross legged and I would sing Beatles songs and suchlike. “Silver Machine” was not in our repertoire. That would have been the summer of 1976. When we’d finished we would go and have tea at the Mountain Grill cafe and look for members of Hawkwind. Four years later, Graham and I found ourselves at the Stonehenge free festival, playing with our own psychedelic band, Treatment. Although I felt welcome and at home, I knew I was just a tourist amongst the TeePee people, the Tibetan Ukrainian Mountain Troupe, the Here and Now/Alternative TV hippie punks. These people were full time. And there were Hawkwind, of course. Playing a three hour set with all the hits – “Hurry On Sundown (“see what tomorrow brings. Well it may bring war…”), “Master Of The Universe” et al. For awhile there, it seemed like they were following me around. Every free festival I went to, there they were. Reliable, you might say. Then free festivals were outlawed in the most vicious way possible by the Thatcher administration (“The Battle of the Beanfield”) and I never saw Hawkwind again.

For fans of the group, the history and development has been well documented. Anyone who wants to knows where to look. For me, listening to “In Search Of Space” now conjures up a very strong, intoxicating and specific atmosphere that I remember as being something that I very much wanted to join in with in my early adolescence (when it was already all but over). There’s something compelling about it. I realise now that the reasons I took Hawkwind for granted back then were actually their strengths. They were reliable. Their lack of instrumental prowess a kind of do-it-yourself, self-taught, pre-punk swipe at all the Rick Wakemans and the John McLaughlins. You don’t have to be able to play all those notes. Just tune up, tune in and go. If the music was uneasy it reflected uneasy times but still it reflected a community. In this, they were triumphant in a way that is quite inconceivable nowadays. Hardly surprising then that it evokes nostalgia.