Category: Writing

-

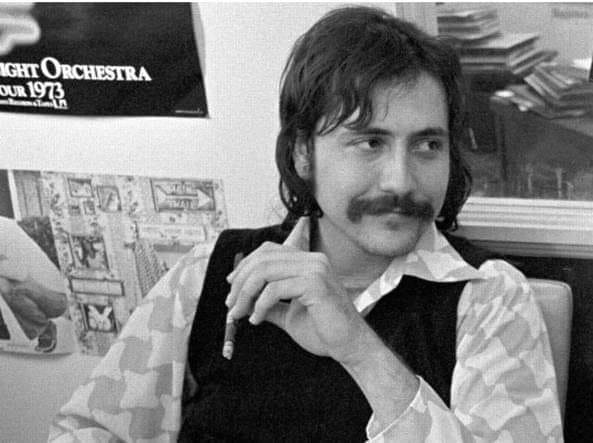

Public Image Ltd 1st album

Listening to the first Public Image Ltd album all the way through in honour of Keith Levene. I probably haven’t done this in 40 years. A few thoughts. The opening track (posted here) is actually one of the most oppressive pieces of music I’ve ever heard. It’s almost impossible to overstate how shocking it was in 1978. The length of it, the intensity of the sound, the absolute commitment to relentless misery. The bass was deeper than anything heard on a rock record before. Of course it’s easy to see that Wobble had adapted it from dub but most rock fans didn’t listen to dub in 1978. Similarly, the heavily flanged guitar. Now we know it’s a flanger pedal – since it became so overused by every guitar player who wanted to sound ‘modern’ in the wake of this – but then it sounded like some horrible alien was torturing the guitar. There were no real precedents for this. Lydon’s howling in pain remains archly English, underlined by his final pronouncement: “terminal boredom”. That anyone would want to make a record like this, and then put it out as track one, side one of your debut album. Surely there had been no more definite declaration of intent since “Black Sabbath” kicked off “Black Sabbath”, the first album by…Black Sabbath. But scary as that was, it was a cartoon scaryness. This is just grim: staring into the void until you get bored. Terminally. When the album came out, Lydon got a lot of flak for “Religion” – his unaccompanied poem attacking the Roman Catholic church. It wasn’t good poetry, it was unnecessarily offensive etc etc. At this distance it seems like a pretty valid commentary. Lydon hates the Catholic church and all that it stands for with extraordinary venom. He makes that abundantly clear and, as someone brought up in the Catholic church, he surely has every right to state his opinion. The music that lurches in to accompany the poem is angular and lopsided, almost Beefheartian, but where Beefheart lopes and glides, this stabs and slashes. It’s nasty music. The intensity is brought to a peak with “Annalisa” – the closest this album gets to straight rock music. The riff and driving drums might be off The Stooges “Fun House” but the bass is so deep it constantly threatens to upend the track. Lydon relates the horrifying tale of a 15 year old girl who was starved to death by her parents who were convinced she was possessed by a demon. Back then, my friends and I would revel in the ‘heaviness’ of this track, something we could relate to and enjoy, but now it just sounds frankly terrifying. It fills the room with an evil energy and it is really quite a relief when it’s over. Over on Side 2, the single “Public Image” has been overpraised lately by ageing critics grateful for something they can wholeheartedly enjoy and recommend. Don’t be fooled. It may have a pretty tune but it’s still “paranoia you can dance to” – to quote John Peel’s memorable phrase. “Low Life” and “Attack” slip past like a pair of half finished demos, and then there’s “Fodderstompf”. This presented quite a problem at the time, perhaps not unlike Elvis Presley singing “Old Shep”. Did him singing it make this maudlin old ballad rock’n’roll? Did Lydon and Wobble being risibly silly screeching “we only wanted to be loved” in a studio for seven minutes constitute “post-punk” (whatever that was)? Time has been remarkably kind to “Fodderstompf”. The actual track was way ahead of its time. A very catchy bass line endlessly repeated over a slightly phased disco beat. Apparently it became a camp hit at Studio 54 with drag queens singing along with it at the top of their voices. In itself, this might be the most relevant thing about this record. Looked at another way, it’s shameless padding: a bunch of drunken druggies armed with a major label budget run out of ideas. Never mind. This album changed the landscape of British music. It’s very much a matter of opinion whether it was a good or a bad thing. Myself, I doubt if I will ever feel the need to listen to it again. But I’m glad it’s there. -

I Was A Teenage Cannibal!

I’m going to write this down while I still remember it.

I’d like to apologise in advance to anyone who’s feelings I hurt, or who feels left out – or who wishes they’d been left out.

Also, of course, for stating my opinions as facts.

Also very grateful to have my facts corrected by anyone who remembers things better than I do.

Like a lot of rock’n’roll stories this one begins in the Summer of 1976. I had just turned 16 and had a Saturday job handing out flyers for a shopping mall named the Antique Hypermarket on Kensington High Street. I had to bicycle there for 10am on a Saturday morning, fill my shoulder bag with flyers, cycle to the top of Portobello Road and hand them out to the milling throngs of tourists until the flyers had all gone. It only paid £2 an hour but it was great for people watching. The first time I saw Punks they looked like they had arrived from another planet. At that time, most people dressed like members of Abba or Stevie Nicks’s Fleetwood Mac. When I finished handing out the flyers I would wander down Portobello Road to the poorer end and check out all the record stalls. I was totally obsessed with music, as always. At the time I was going through a Led Zeppelin/ Queen/ Thin Lizzy phase. In those days, most boutiques had a record stall concession and the one in the basement of 253 Portobello Road particularly interested me because it sold bootlegs. The proprietor was a friendly soul who would let me listen to his wares even though he knew I usually couldn’t afford to buy anything. One Saturday I went downstairs to this stall to hear a highly spirited version of “Route 66”. I knew the song from the Rolling Stones first album but this was something else entirely. Fast and furious and enormously urgent. It was followed up by a short snappy tune with a killer guitar solo. I inspected the turntable. It was an EP – an Extended Player. A 7” 45 with two songs on each side. Even in 1976 this was an anachronism. EP’s had been popular in the 1950s and 60s, aimed at people who couldn’t afford the LP, but they had fallen into abeyance by the end of the 60s. I looked at the friendly bootleg vendor, he was smiling all over his face. He turned the record over. “Beautiful Delilah” – a song I knew from the first Kinks album, but again, this version kicked like a mule in comparison. “Teenage Letter” followed – absolute mayhem. Ferociously fast, with a guitar solo to compare with Dave Davies at his most berserk. The friendly vendor turned it over. And over again. I must have listened to it three times before I left. I made a mental note of the title: “Speedball” by The Count Bishops, before scurrying off to buy a cheap 2nd hand copy of “Aftermath” by The Rolling Stones.

“Speedball” bugged me. It got under my skin. I wasn’t sure about it. It seemed like a dam about to break. Talking about it at school with my mates, it turned out that someone I knew who was a couple of years older had a half-brother who managed The Count Bishops! Pete Manheim. Blimey! For some reason that clinched it. The following week I went back to my bootleg vendor but my man had sold out of “Speedball”. So I went to Rough Trade on Kensington Park Road and picked up a copy there. I took it home and played it into the ground. Suddenly Queen and Led Zeppelin didn’t seem to have the same allure. At this point in my life I had just managed to inveigle myself into the school rock’n’roll band, Captain Comedown, by getting them a gig on condition that I got to play with them. This I did. The band were not unusual for the time in being primarily influenced by the likes of Lynyrd Skynyrd and Bad Company. I didn’t mind playing this stuff, as well as I could, which was not particularly well, but looking back I can see that “Speedball” marked a big change, not just for me but for British rock’n’roll in general. (Ironically, as I learned later, only one member of the Count Bishops was British). I listened to the way Johnny Guitar and Zenon de Fleur played and thought: I could do that. Actually I couldn’t – yet – but I thought I could, with practice, whereas I never for a moment thought I could play like Brian May or Jimmy Page. The difference is critical. I practiced. And practiced. I quit school in December 1977 so that I would have more time to devote to the task. I read up about The Count Bishops in the music press. Apparently at their gigs they liked to play the songs on the first two Rolling Stones albums, in correct sequence. This was the kind of monastic, obsessive attention to detail that I could relate to. I had the first Stones album, I obtained the second one and got stuck in, learning all the licks I could from them both. I still maintain that this is an excellent apprenticeship for learning to play rock’n’roll guitar.

Then Punk arrived in all its tatty glory. Autumn/ Winter ’76, the whole of ’77. London was a very exciting place to be. I was very fortunate to be there. I was a little bit too young to get in to the gigs to begin with, but that got easier as I turned 17. I never actually adopted the Punk look. I didn’t particularly like it and I did not want to be a ‘Middle Class Poser’. It would be unseemly. But I certainly bought as many of the records as I could and went to as many gigs as I could. It was a great time for going to gigs. They could be free, or 50p to get in; 75p or £1 for a ‘name’ act. Two bands, sometimes three. Even if the bands were rubbish the chances are that they would be fun to watch (I’m thinking specifically of The Warsaw Pakt and Ed Banger and The Nosebleeds here). And of course, in the middle of all this, there were The Count Bishops. Gigging away, putting out singles and trying very hard to keep up with what they had, in some ways, started. It must have been tough for them to see all these twits in safety pins and spiky haircuts getting so much instant attention but they seemed to have found their niche on the rapidly changing London gig circuit. I used to go and see them every chance I got and I would position myself in front of Johnny Guitar and watch his fingers like a hawk. “Oh God, that kid’s in again”, he must have thought if he noticed me at all. The Count Bishops could never be a Punk band, no matter how many Punk bands they shared stages with. Their roots were solidly 60s UK R’n’B. But they had leather jackets and relatively short haircuts and AC-30 amps and they made fine, fierce music. In the eighteen months or so since “Speedball” had come out they had gone through some changes. Mike Spenser, their former singer and leader, had left the band. They had carried on as a four piece for awhile, putting out the marvellous single “Train Train”- written by rhythm guitarist Zenon de Fleur – but had felt the need for a frontman. So they imported Dave Tice from Australia to be their new singer. Tice was much more of a traditional kind of Rock singer. He must have been amazed at the Punk goings on in London when he arrived, but he got on with the job and they put out an album in the Summer of 1977. Listening to it now, it’s got some nice tracks on it. It is a punk album in the original sense (hence the small P) but it seemed rather old-fashioned at the time. Nothing on it had the timeless urgency of “Speedball”. But I liked it. I felt a certain loyalty. I saw The Bishops (as they were always known) here, there and all over the place. They always put on a good show. I got chatty with Paul Balbi, their drummer, who seemed the friendliest. He was also Australian and had been instrumental in bringing Dave Tice over. Balbi lent me tapes of rehearsals and studio sessions. I mean, Wow… He trusted me with them. Just a really nice guy (and a very good drummer, his hi-hat splashes being a kind of signature).

Meanwhile, Captain Comedown were getting a few gigs around town. We were never going to be a Punk band either but we sort of fit in by virtue of youth and inexperience. We were noisy, brash and full of ourselves. We got a gig at The Roxy, long after its prime, on a bill with two other bands, one of which was named Bodies and who were by far the most useless band I’ve ever seen. They were a three piece – two guitars and drums. One of the guitars was a home-made double neck. They wore white boiler suits. They could not play. I mean, they really could not play. The guitars were out of tune with themselves and each other. The drummer could not keep time. They attempted to play David Bowie’s “Suffragette City”. I have not forgotten them. We got up to do our set. The place was pretty much empty but a couple of bored looking blokes dressed as Punks hung around the front of the stage. One of them spat at me. He missed. I smiled at him. Possibly this was not the correct response. We got through it and, incredibly, the management offered us another date. We accepted gratefully. At no time did anyone mention money. But when it came to the date in question we arrived with all our gear to find the Roxy had closed. Shut up shop. Nobody home. Nobody had bothered to tell us. Being enterprising lads, we wandered down the street to the Rock Garden to see if maybe we could get a support slot there that night. “Fine by us if the headliners don’t mind”, we were told. And who were the headliners? Yep. The Count Bishops. So we got to meet them. I mentioned Pete Manheim. “You just lost the gig”, said Johnny Guitar. I nearly died on the spot. Fortunately he was joking. I renewed my chat with Paul Balbi. I asked him what had happened to Mike Spenser, the original singer. Balbi filled me in. Spenser had left under a bit of a cloud. There were no ill feelings but he was apparently not the easiest guy to work with. He had formed a band called The Cannibals and had put out an Indie 45 named “Good Guys” in a brown paper hand printed sleeve which he sold at his daily job at the Magic Bus company in Shaftesbury Avenue. Then The Cannibals had just left Mike holding nothing but the name and gone on to form a new band named The Inmates. And thus it was I heard the magic words: “he’s looking for a guitar player”. I immediately expressed interest. Paul grinned. “He’s got a heavy Brooklyn attitude”, he told me. I asked him if he would mention me to Mike, give me a number to call. He said he would.

The very next day I headed down to the Magic Bus company in Shaftesbury Avenue. Magic Bus was one of those companies that regularly advertised in what remained of the Underground press. It was a leftover from hippie days. You could travel to Amsterdam or Paris by bus very cheaply. Also, overland to Morocco or even India. You get the idea. On this day, its office was very crowded. “Hope y’all broughtcha sleepin’ bags” I heard an unmistakable New York accent say. That was my first brush with Mike Spenser. I bought a copy of the “Good Guys” single off him but didn’t have the courage to mention wanting to play guitar for The Cannibals. I went home and played the record a lot. On the ‘B’ side was a slow R’n’B ballad named “Nothing Takes The Place Of You”. It was beautiful. So I left Captain Comedown and phoned the number on the 45 sleeve. On the phone, Mike was non-committal but not unfriendly. We arranged that I should turn up for an audition of sorts at the squat in Clapham where he was living. I brought with me two musician friends for moral support: David Catlin-Birch who went on to become a successful professional musician, and Graham Cronin who later transitioned to Gail Cronin and tragically died of cancer. (I later played with Graham in an early version of TreaTmenT.) At Mike Spenser’s front door in Silverthorne Road, Clapham, I was very nervous. We rang the bell and nothing happened. We rang again. After a couple of minutes Mike appeared with us at the front door. He must have come from a side entrance. He looked us up and down. Lambs to the slaughter. He suggested we convene in the pub up the road. So we did. Mike was smaller than I expected, about my height (I’m 5’8’’), curly black hair, dark piercing eyes. Completely undiluted Brooklyn accent. To us three, he presented a formidably exotic figure. Over a couple of pints, Mike explained that he had a drummer and two guitarists but needed a bass player. My heart sank. I was too late! But we talked music music music and I think Mike was impressed by my references. Turned out that one of his two guitarists was an older man who only wanted to play blues. While Mike enjoyed this purity it wasn’t entirely what he had in mind. So we had an audition in the basement of Silverthorne Road. I remember playing the licks to “Cry To Me” – the Solomon Burke ballad that The Rolling Stones had covered on their 3rd album “Out Of Our Heads” – and I could see that Mike enjoyed singing that. It turned out that Mike had left the Count Bishops in a huff over their refusal to put their recording of “Cry To Me” on the “Speedball” ep. It wouldn’t have fit, it wouldn’t have worked, it would have diluted the effect enormously. But Mike wasn’t having it. He wanted it on there and, actually, when he played me the acetate of it on his ancient stereogram, it sounded pretty damn good. If I’d been paying close attention, however, this tale might have sounded an alarm bell or two, but I wasn’t paying close attention. I was having a great time. I felt like I was passing an exam with flying colours.

Mike gave me the skinny on The Count Bishops. The name came from a legendary New York street gang. Mike and fellow American Johnny Guitar had had a hardcore R’n’B band back in the States called The Kingbees. They were united in their love of the early Rolling Stones, Them, The Yardbirds The Animals – British R’n’B bands of the 60s. This was completely unfashionable at the time, on both sides of the pond but this just gave Mike and Johnny a deeper edge to their devotion. Then, for reasons unclear, Mike had de-camped to London. Wasting no time, he had found rhythm guitarist Zenon de Fleur (a Polish gentleman, real name Zenon Hierowski, the name de Fleur had emerged following a binge: “haw haw, lookat Zen on da floor”), English bassist Stevie Lewins and Australian drummer Paul Balbi. Thus assembled, Mike got on the phone to Johnny in New York and cajoled him to come to London to complete the line up. Thank God he said yes! Mike’s reputation had preceded him across the Atlantic. He had been a roadie for The New York Dolls in their final days and had not escaped the attentions of the beady eyed Malcolm McLaren. McLaren turned up to one of the very first gigs of the newly formed Count Bishops and offered Mike the job of singer with this band the Sex Pistols that he was putting together. Thank God he said no! Wearing their R’n’B purity on their sleeves, The Count Bishops began by playing lunchtime gigs in record shops rather than the pub circuit. Here it was that they would sometimes play the first two Stones albums in sequence. Such devotion quickly attracted the attention of Roger Armstrong who ran Rock On records in Camden Town. Armstrong was setting up an independent record label named Chiswick and he signed the Count Bishops to a recording contract. Emboldened, even vindicated, they went to Pathway Studio, an 8 track in Islington, and laid down a righteous 13 song demo, four of which were selected by Armstrong to be the label’s first release. Mixed and mastered, “Speedball” the EP came out in December 1975. It remains one of the best and most uncompromising rock’n’roll records ever made in Britain. Anyone who doubts me has only to listen to it. It was the first significant indie label record to be released in the 70s and it presaged a flood of similar releases, most notably The Damned on Stiff.

Back at Silverthorne Road, Mike dumped the senior blues guitarist and installed me: 18 year old mouthy flash git with a newly acquired cream coloured Gibson SG. He asked if I knew any bass players. I said I’d look into it and persuaded my running buddy Paul Hutchinson to buy himself a bass guitar and a bass amp and get learning. He picked up a beautiful Epiphone Rivoli and a vintage Gibson bass amp and got to work. That’s how easy it was in those days. Paul Hutchinson and I had attended the first UK gigs by George Thorogood at Dingwalls earlier in the Summer and we were full of the righteous cause of Rhythm and Blues. Paul had picked up Hound Dog Taylor’s “Beware Of The Dog” live album and we played it constantly. Paul proved to be an extremely quick learner. The other guitar player was Johnnie Walker. Slightly older, innately sensible, impeccable rhythm, Johnnie was old school. None of this Punk Rock foolishness, Johnnie played like Keith Richard before he put the S back on the end of his surname. Rarely ever taking a solo, when he did he sounded like a combination of Wilko Johnson and Syd Barrett. But Johnnie was cool. Mr Reliable. Over there on the drums, the unique Sion Evans. Sion (pronounced Shawn) was from a little coastal Welsh town named Fishguard. He was the same age as me but from a completely different world. Unreconstructed to a fault, how he and Mike communicated was something to be savoured. How they understood a word the other was saying was in itself miraculous. Sion had a drum set that had to be seen to be believed. Bits of old barrels, tubs, biscuit tins, broken cymbals – but he could play it! He had a great sense of rhythm and when he clattered into a song you knew he meant business. So we got down to it: me, Mike, Paul, Johnnie and Sion. Mike had a bizarre Italian PA set up. It was falling to pieces but it worked. I needed to buy a decent amplifier and in my ignorance acquired a new Marshall transistor combo. Mike was appalled. He demanded I take it back and get something better. So I did. In Charing Cross Road, I found a 1964 Selmer Zodiac Tru-Voice 30w combo for £70. Perfect. I had my sound. We worked up a set and by the Autumn we were ready to start gigging. I’ll never forget after a chaotic but complete version of Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen”, Mike broke into a broad smile and said, as much to himself as to us, “we’re a band, we can play rock’n’roll.” Mike could be so charming at times. You just wanted to please him. He was an exotic to us British kids. The real deal. “A genuine American Rhythm’n’Blues singer”, as my friend Clive described him (more of him later).

Mike made some calls and got us some gigs. Sharing the Silverthorne Road squat with him and his lovely girlfriend Mandy (sister to the Inmates guitarist Tony Oliver) was a tall thin Irishman named Phil who ran a 2nd hand record stall in Soho Market (where he employed a young lad named Shane McGowan). One night I crashed on the sofa and Phil gave me “Nuggets” to listen to. Another vital plank in my education. I think it was through Phil that we got our first gigs supporting a French band named Gino and the Sharks. We needed a van. Mike borrowed £90 off my sister (which he scrupulously repaid) and bought an old banger of a van. Mike was a genius car mechanic. He really knew about engines. We were on the road. Then, a mere six weeks after Paul had started learning bass guitar, Mike booked us into Pathway Studio to record a single. October 26th 1978. To say I was excited would be an understatement. We recorded four songs: Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “Nadine”, The Rolling Stones “Flight 505” and an original titled “Baby You Can’t”. We ditched “Flight 505” and settled on “Nadine” to be the ‘A’ side with the other two on the ‘B’ side. Mike put together a paper sleeve with an x-ray of his skull on the front and crudely mimeographed photographs of the five of us on the back. It all happened so fast. It came out on Mike’s own Hit Records with a yellow label, a first press of 500 copies. I was so proud of it. Actually, listening to it now, it’s quite a record. Where Chuck Berry’s original is a lithe and sexy car chase, ours is like an unstoppable tank trundling along, flattening whatever gets in its path. Paul’s bass is sub-sonic. How we got that much bass on to the cut amazes me. Pathway was essentially a mono studio, a relic even then, and this record sounds like nothing else. Johnnie’s intro chords cut like razors and I was pleased as punch with my best Keith Richard solo. Sion’s drums go thwack, thump, crash! Mike cajoles and pleads – “oh honey, where are you?” It’s great. I can listen to it now and thoroughly enjoy it. Promoting it at the time, I marched into the New Musical Express office on Long Acre and demanded to speak to Charles Shaar Murray. I had met him, and chatted with him, at the George Thorogood gigs and he had used me as a device in his piece on Thorogood – describing me as typical of the kind of kid who was deserting Punk for R’n’B, the upcoming ‘Blue Wave’ that he was eager to bring into being. Thus I felt that by bringing him a copy of the new single I was somehow keeping my end of the bargain. Murray emerged, looking somewhat the worse for wear, and pretended he remembered me. He took the single. “Oh you’re working with Mike now?” he said, and I felt like I was in. And he reviewed it, bless him. There it was, in the next week’s singles reviews in the NME. “Ballsy but indistinct”, he said. That would do me. The importance of a review in the NME at that time cannot be overstated. Thus we could get distribution in all the Indie record shops. The 500 copies would be sold. The sweet smell of success. There might even be a second pressing. On another front, trying to get us on the radio, Mike took me with him to visit Charlie Gillett. Mike sold “Nadine” to Charlie Gillett like it was the greatest record ever made but Gillett was not impressed. “Haven’t you got any original material?” He asked, not unreasonably. Oh yes! Flip the record over and there was “You Can’t”. Such an original. “Oh yeah,” said Gillett, “have you told Bo Diddley?” You win some, you lose some.

Out there in the rest of the UK music scene, many things were happening. Punk was yesterday’s stale potatoes but its ramifications and ripples continued on – as they do to this day. The music press was omnipotent but not always right. A concerted effort to start a Power Pop trend with bands like The Pleasers – dressed like Gerry & The Pacemakers c.1963 – completely failed. Ian Dury had a No.1 hit record with the marvellous “Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick”. Two Tone was getting underway in the Midlands – a bona fide grassroots working class movement featuring The Specials, The Beat, The Selecter etc. Back at the drugs’n’attitude, Public Image Ltd were declaring Rock to be dead and lots of people believed them. A whole new slew of misery merchants came up in the wake of Joy Division. NME employed Ian Penman and Paul Morley to further alienate their readership with quotations from Foucault and Nietzsche. Madness and Squeeze began having hits with completely English songs that recalled the heyday of The Kinks. It was a very fecund time. Sometime at the end of 1978, we got a gig at the Moonlight Club in West Hampstead supporting a new band named The Pretenders. I’ve written about our experiences with The Pretenders elsewhere so let’s just say it was very exciting. They were obviously going to be very successful and it felt like we were in on it somehow – even though we weren’t. Oddly enough, Mike was always deeply suspicious of other Americans so he never really clicked with Chrissie Hynde.

In the midst of all this, Charles Shaar Murray’s ‘Blue Wave’ was taking shape in the clubs and pubs of London. Apart from us, there were The Inmates – the former Cannibals who had re-grouped themselves around the formidable talent of singer Bill Hurley. Taking their cue more from The Animals than The Stones, they were far more polished than us and obviously primed for a record deal and any number of professional engagements. We did many gigs with them and I always enjoyed watching them do their thing. In those days, they would open their set with Eddie Cochran’s “Jeannie Jeannie Jeannie”. They would do Otis Redding’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water” and Wilson Pickett’s “Danger Zone”. Their first single – the Vic Maile produced “Dirty Water” – was a peach and summed them up perfectly. Murray’s own Blast Furnace & The Heatwaves could always be relied upon for a good rocking set. I remember copping the intro to Chuck Berry’s “Back In The USA” by carefully watching Murray’s fingers on his Stratocaster. His harmonica player called himself Skid Marx and this I thought captured both the humour and the politics of the scene rather well. They were fun and they could rock. From the same Canvey Island cradle that had spawned Dr Feelgood there was the Lew Lewis Reformer. They were probably the first blues band I ever saw live. Lewis was a speed freak and a Little Walter devotee. Rail thin, manic and slightly terrifying, Lewis wore Oxfam suits, braces, sported a razor haircut and kept his harps in a pint of lager. They would do Little Walter’s “Watch Yourself” with a strut and the swagger of a knife fighter. Tough stuff. He could really play. Lewis’s first single appeared on Stiff Records: “Caravan Man” b/w “Boogie On The Street” and it remains a little classic. Lewis eventually got four years jail time for holding up a Post Office with an imitation pistol. That was him. If Lew Lewis provided a sense of manic danger, The Commuters were pure knockabout. Hailing from Hemel Hempstead, they called themselves The Commuters because they spent so much time commuting between Hemel and Euston. They had a residency at the Pegasus in Green Lanes in Stoke Newington and I remember Paul and myself dragging Mike out there to see them. They were a great live band. Lenny, the lead singer, gave it so much front. Lu, the man mountain bass player, looked like a psychopath. Tim the guitar player, tall and spindly, was the only one who seemed to know what he was doing musically. Greg the drummer sometimes caught the groove, sometimes not. Pete the harmonica player played through everything, much to Tim’s annoyance. But the point about The Commuters was that they had a completely chaotic wild enthusiasm. They steamrollered through Bo Diddley’s “Roadrunner” which you might have expected, but they also did a Supremes number, for God’s sake, and an Aretha Franklin cover. Anything less like The Supremes or Aretha Franklin than The Commuters it would be hard to imagine. They also ran roughshod over Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight”. They had a few originals: “It’s Your Round Girls” being a particular favourite. Also, the wonderful “Bubble Car”. The Commuters inspired love in their audiences and we were duly smitten. Offstage, they were complete sweethearts, if utter pissheads, and an alliance was formed. We did many gigs with The Commuters. The Dublin Castle in Camden being one, and another being a club in Bicester where we were given the run of the place and paid in beer. All we could drink. Oh God… The Commuters drank us under the table. I remember playing guitar while propped up against the wall, praying for it to end. But I always was a lightweight.

Perhaps I ought to say a word or two about Dr Feelgood. I had been a bit too young to see them in their heyday but it was really down to them that the second wave of the UK pub rock scene got started. At a time of Mike Oldfield and Yes and Genesis, Dr Feelgood had provided a way out. Short hair, Oxfam suits, short songs, attitude to burn, they showed a way forward in the mid 70s. For myself, I could never really get it. I could hear that Wilko Johnson was a remarkable rhythm guitarist, playing a Telecaster through an HH amplifier with his fingers, and I could hear that Lee Brilleaux was a great frontman and harmonica player but the rhythm section were too lumpen for me. It lurched where it should have grooved. There was no colour to the sound. It’s absurd, really. If I’d seen them back in ’74 or ’75, I’m sure I would have been massively excited by them but as it was, I preferred the sons of Feelgood, such as The Commuters or the Lew Lewis Reformer, much more than the Feelgoods themselves. At the time of the scene I’m writing about, Wilko had left Dr Feelgood, to form his own band – the Solid Senders – and had been replaced by Gypie Mayo. They weathered the Punk years and put out album after album, playing to their devoted audiences, and by the time The Inmates (say) put out their first single Dr Feelgood were almost as much of a Rock institution as Thin Lizzy. Not in that league commercially, of course, but as well established. You couldn’t go down to the Nashville or the Hope and Anchor, have a couple of pints and watch Dr Feelgood and that is really the difference. You could watch The Pirates, though, featuring Wilko Johnson’s childhood hero Mick Green on guitar. Veterans to say the least, they clattered and thumped at a very high level of proficiency. Likewise Dave Edmunds Rockpile, who were a bit too rock star really for this scene. Dave Edmunds had had a No.1 hit record after all, at the beginning of the decade, and he was signed to Led Zeppelin’s Swansong label. On bass there was Nick Lowe, star producer and hit songwriter, and there on drums was Terry Williams, soon to be whisked away to real stardom with Dire Straits.

No girls. No girls at all. Not a single one of these bands had any girls. Such a sweaty boys club. Beer, fags, armpit dressing rooms, dirty jokes. It was all very blokey. At the time, I didn’t give this a moment’s thought. I’d been to an all boys school, after all. I knew how to muck in. Girlfriends did not generally venture backstage.

Back down on the ground on the Cannibals front, everything was going great guns until one evening I got a phone call from Paul Hutchinson. “I’ve decided to leave The Cannibals”, he said. And I never really understood why. I couldn’t talk him out of it so now we needed a bass player again. I went to see my old mate Clive Leach who had been the bass player for Captain Comedown. He was in. We were back up and running, playing the newly opened 101 Club in Clapham, the Moonlight Club in West Hampstead, Dingwalls in Camden. And then, Sion decided to quit. Damn it. That was a real setback. Sion was unique. And again, I couldn’t figure out why.

But before Sion left, we played a very poignant benefit gig with The Inmates at the 101 Club for the family of Zenon de Fleur. Zen had got killed in a car accident. It was a great tragedy. Apart from anything else, it severed the hamstrings of The Count Bishops. Zen had been absolutely central to their sound. They struggled on without him for a little while but without his powerhouse rhythm playing, they sounded like shadows of their former selves. Zen died on March 17th 1979. Then Paul Balbi got deported for overstaying his visa and that was definitely that. A very sad end to what had been a great rock’n’roll band. Before all that happened, though, it had looked rosy for a brief moment. The Bishops (as they now officially called themselves) got on Top Of The Pops with their version of “I Want Candy”. They put out a live album (“The Bishops – Live”), a second studio album (“Cross Cuts”) and toured with Motorhead. They looked poised to become a rock’n’roll institution when fate struck them down so cruelly. Later on, when I got friendly with Stevie Lewins, he lent me a Dutch bootleg album named “Good Gear” which had been recorded in 1976 when they were briefly a four piece after Mike first left. It was a nice album, rough round the edges. No professional polish but a lot of feel. Now it’s hard to find. Poor old Count Bishops, relegated to a footnote in the history of UK Rock. But in their day, they were most mighty and righteous. I will always remember them with great affection and respect.

Back at The Cannibals, we needed a drummer, and fast. We had gigs to do. So we held auditions. Oh Lord… Anyone who has ever auditioned drummers has my eternal sympathy. Thick and fast they came at last, and more and more and more. In the end we settled on Gary Stannard. Gary was my age and he could really play. A Keith Moon devotee, he rolled and paradiddled his way around our material with consummate ease. Mike initially thought he was too flash but I persuaded him. Gary was fun and raring to go. He was in. He added musical muscle to our sound. We got a residency at a big pub in Clapham named The Two Brewers and were beginning to build up a real following. Then we got fired for playing past last orders. It happens. Listening to the ragged tapes of those dates I’m struck by how horrendously out of tune we were most of the time. E – B – E – G# – B – E go the guitars, over and over again, trying to find a common pitch somewhere relative to the vicinity of 440hz. I was far more guilty than Johnnie. He had learned to turn down when tuning up. I had not. Never mind. The audiences didn’t seem to care. The phoney Mod revival was now well under way and we had started to do Small Faces numbers and The Who’s “Out In The Street”. My SG still bears the scars of where I used to pretend I was going to smash it. What a little twit I was. It’s funny. I always thought we were strictly a Rhythm and Blues band but really we were a noisy punk band (with a small P) playing R’n’B material. Mike knew what R’n’B was supposed to sound like but he was developing his own uniquely demented vision of what he wanted to do with it. Back in our earliest rehearsals, Mike had loaned me albums by Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed, Mississippi Fred McDowell. This was a real education. But I couldn’t play like that. I could do a passable imitation of Steve Marriott on the first Small Faces album, however. As well as Keith Richard, of course. That apprenticeship was still my bedrock.

Mike took us back into Pathway Studio to record our next single. He had a song left over from the original Inmates/ Cannibals days that he wanted to record: “I Could See Right Through You”. Plus, he and Johnnie had started writing songs together. They had come up with a song named “Pick’n’Choose”. The lyrics to these original songs were written from the point of view of the endless battle of the sexes. Girls were always out when Mike called, bugging him when they were in, chiding him for his infidelities, acting stupid, wanting commitment etc etc etc. Essentially, it was a stance adapted from The Rolling Stones “Stupid Girl”. Petulant misogyny. It was out of date then, leave alone now, but I hadn’t really noticed. At Pathway, rather than concentrate on getting the best versions of these songs down, we simply recorded everything in our repertoire. 31 tracks in four hours, breaking the house record. I had just spent the princely sum of £285 on a second-hand Rickenbacker 12 string and I wanted to overdub it on as many tracks as possible. Never mind that it was impossible to tune! I should mention that I had written a couple of ‘original’ songs with Mike too. One was a rip-off of The Beatles “Day Tripper”, the other was a rip-off of The Kinks “You’re Lookin’ Fine”. To the first, titled “Just For Fun”, Mike had written a really quite forceful denunciation of the Ruling Classes. This was something of a departure and I remember people in the front row of our gigs at The Two Brewers singing along to it. The other, titled “Lucky Charm”, was a detailed description of an eccentric girl who covers herself with superstitious paraphernalia. This business of original material was quite interesting. As these bands I’ve described all pretty much started out raiding the back catalogues of The Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, Animals etc the question of original material didn’t really come up until they started getting record deals. (I should note that Blast Furnace & The Heatwaves adapted Robert Johnson songs.) Then it suddenly became all about the publishing and original material was demanded. Thus would descend the ghastly spectre of Rock. Rhythm and Blues is black American music, even when filtered through pimply white youths misunderstanding it. However, these pimply white youths had no reference points beyond these misunderstandings of the source material and in most cases (like myself) had grown up learning to play Rock music. It’s interesting now, 45 to 50 years later, how incredibly dated the Rock of the mid to late 70s sounds, whereas the R’n’B of the 1950s and 60s still sounds vital.

So we mixed and mastered “I Could See Right Through You” b/w “Pick And Choose” but for some reason, possibly lack of money, Mike did not come up with a picture sleeve. This meant we couldn’t get distribution, despite a glowing review in the NME from Tom Robinson of all people. I think the single sold about 50 copies. We carried on gigging. The Hope and Anchor, a pub in Islington that regularly featured all the bands on the scene, decided to host a festival and did a deal with Arista Records to put out an album of the best of the sets they would record. We chose a track from our set to be included but they overruled us and put out a version of “Just For Fun”. This got a great review from The Morning Star – which was very gratifying. The album, “The London R & B Sessions”, if you can find it, is probably the best snapshot of the UK Pub Rock scene at the end of the 70s. Stealing the show by a country mile was Wilko Johnson with his berserk tribute to Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

The Pretenders began a residency at The Marquee. Every week for a month – November 1979. I went every week. I was a shameless, gushing fan. It was beginning to dawn on me that there was something most definitely missing on the London Pub Rock R’n’B scene: Sex. I wrote a fan letter to Chrissie Hynde and begged her to let us, The Cannibals, support her, The Pretenders, the next time they played at The Marquee. Incredibly, she wrote back and said: Yes, by all means. You can do both nights. Wow… We were booked in to play December 22nd and 23rd. There was one snag. The Inmates had been playing a nightclub in Paris called The Gibus Club (funnily enough so had The Pretenders but I didn’t know that then). Their manager had very kindly arranged for us to follow on and do a week there too (the fact that The Inmates had a proper manager and we didn’t was lost on me at the time). We were supposed to be leaving on December 23rd. What? How could anything be more important than supporting The Pretenders at The Marquee? Mike didn’t seem to be particularly enthusiastic but somehow, the logistics were sorted, ferries changed etc. Our two nights at The Marquee went off OK. The first night we had all our friends and fans in and it felt like a real occasion. A high watermark of sorts. The second night was a bit of a damp squib. Chrissie Hynde had the flu. I got to hang out backstage with the rock stars. James Honeyman-Scott was lovely. He liked my Rickenbacker. Pete Farndon though, he was obviously trouble. Steve Peregrin Took (of all people) turned up and immediately keeled over. He was a big guy. He fell hard. It was definitely time to leave. In Paris, we had a blast. The French really dig rock’n’roll. They can’t play it but they really like it. “Vince Tayleur!” went the cry. If we’d had any sense we would have learned “Brand New Cadillac” and played it every set. We’d have gone down a storm. As it was, we played two sets a night and lived in a sleazy boarding house that Gary convinced us was run by an ex-Resistance fighter. We misbehaved. It was all very rock’n’roll. When I got home I slept for 18 hours straight. A page turned.

Clive was putting a band together with his brother Gordon and the aforementioned Graham. Also, lending them class, was a keyboard player named Paul MacWhinnie. Keyboard players were a rarity on the Pub Rock scene. The idea of piano lessons and texture being somewhat alien. Paul Mac had been to lots of Cannibals gigs. He was an old mate. They were going to do only their own material, of a psychedelic flavour. I had attended one of their early rehearsals. “Stamp Out Mutants!” They had the makings of a real attitude and originality. I wanted in. It nagged at me. Clive handed in his notice to Mike who accepted it with good grace. I carried on but my heart was elsewhere. We recruited another bass player, Steve Slack. He was a real talent. Fabulous bass player and gifted songwriter. Lovely guy too. Unfortunately he had a weakness for heroin. It wasn’t very long before he was replaced by Jeff Mead. Jeff is the kind of guy that every band needs: he’s reliable, he has excellent gear which he maintains, he can play in time and in tune, he is easy to get along with. Just a gift. Jeff stuck around in The Cannibals for many, many years. Mike had found his valued assistant. One strong memory I have of this brief period of flux. We were rehearsing in a pub in South London and a black guy got up onstage to sing “High Heeled Sneakers”. My goodness, he could really sing! Turned out that it was Limmie Snell, of Limmie and the Family Cooking – a bona fide American R’n’B band that had had an international hit with a song called “You Can Do Magic”. “What’s he doing here?” I asked the fella who had come in with him. He shrugged. “Isn’t it a bit weird for him?” I pressed on. “Hard to go back to skimmed milk when you’ve tasted cream”, came the immortal response.

The day came. I gave my notice in to Mike. He took it on the chin but I could see that he was upset. I hated to do it but I needed to move on. Bands are very much like relationships. You go through so much together and when it ends, it does hurt. Mike had had so many people use him as some kind of rock’n’roll finishing school. He was older than he let on – basically he lied about his age – and he’d been through it so many times. But the thing about Mike, then and to this day, was that he had an absolutely unshakeable belief in the righteousness of The Cannibals. He had given his life to this thing and his conviction that The Cannibals were a truly great rock’n’roll band, deserving of the highest success, was beyond dispute. The trouble was he had a tendency to rub up the wrong way anyone who was in a position to further his cause. Managers, agents, publicists, A&R men, journalists – they all had tales to tell about Mike. His stubbornness, his intransigence, rudeness etc etc etc. It was as though he resented them for being in a position to offer him what he most wanted. To be one up over him in other words. You have to eat a certain amount of humble pie (ie, bullshit) to get along in showbusiness and Mike just couldn’t do it. So he stayed on the margins. Eventually he turned this into an advantage. He started to describe what he was doing as ‘Trash’ rather than R’n’B and went on to front any number of versions of The Cannibals – deliberately emphasizing the amateurish noisiness of the music. Lots of thrashing and shouting. I couldn’t have handled it but in this way he went on to found a movement of similar bands and held ‘Nights of Trash’ where they would all play. There was a certain crossover with the nascent Psychobilly scene and it proved very fertile for a few years.

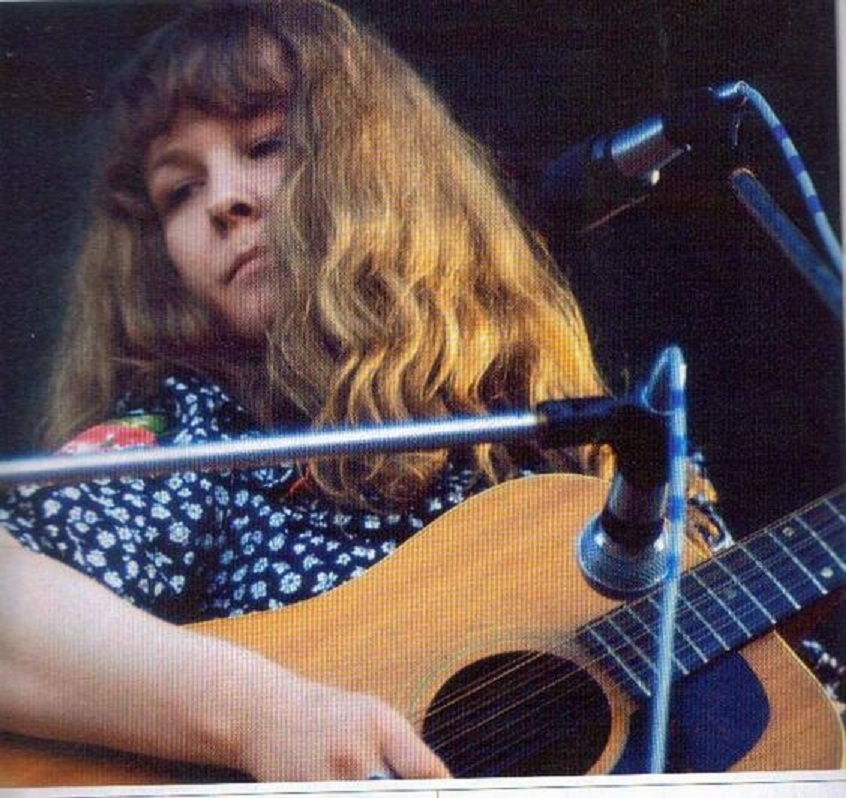

Music was moving on, as music tends to do. The New Romantic scene was unfolding, likewise the Goth scene. No lack of sex there. For myself, perverse as ever, I went off to be a hippy and play psychedelic music with TreaTmenT. The Inner Movie of my life had moved on from 1965 to 1968. The last gig I did with The Cannibals was depping for a guitarist who had gone temporarily awol (the inimitable Mike McCann RIP) sometime in 1982. The gig got reviewed in Sounds and there was a photograph. I had long hair and was wearing a floral satin jacket with round lapels. I didn’t fit anymore. But Mike and I have always stayed friends. Clive rejoined The Cannibals, and left, and rejoined many times. Now Mike is old, and very ill. As I write this, a benefit gig is being held to try and defray his enormous medical bills. Mike phoned me up and asked me if I would come along and play Van Morrison’s “Gloria”. Of course. It will be an honour. “Bring your own lead”, says Clive. “Always bring your own lead.” And there, I feel, may be a lesson in discretion for us all.

-

In Church With The Detroit Cobras

(Note: since this was written Rachel Nagy died in still unexplained circumstances. A tragedy.)

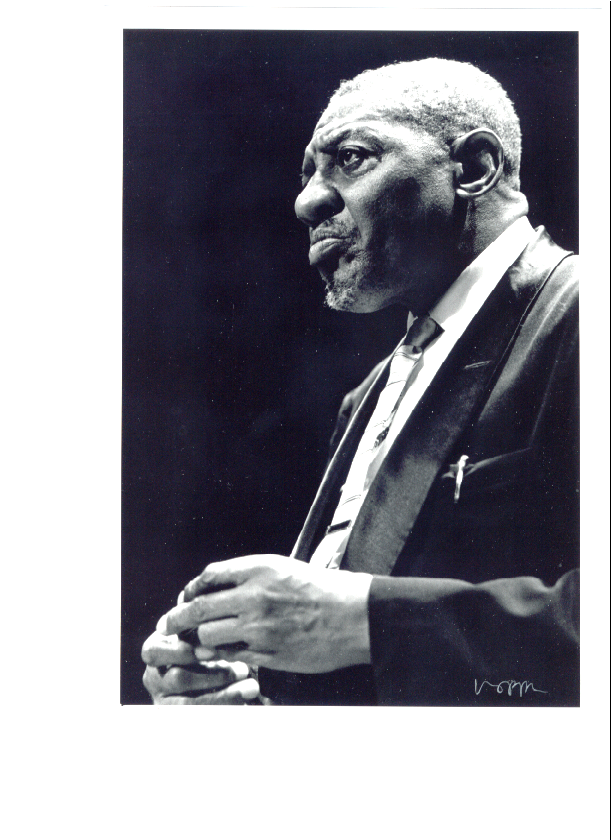

For me, it happened like this. In April 2003 I was getting a lift back from a session gig courtesy of Ben out of Cornershop, who also does press for Rough Trade records. Ben is a true believer in the power of new music. He has never lost his enthusiasm for the excitement of hearing new things. Total opposite to me. Unless I’m forced, I will only ever listen to things I KNOW I like. But I’m getting a lift, so I must be gracious and, besides, it’s invigorating sometimes to be with someone who is so interested in new music – whatever it may be. And he wants to play me something. Thinks I’ll like it. He bungs it on the car stereo. Bass intro, punky guitar, drums – well at least it’s rock’n’roll – but I’m already worrying that it’ll just be some kids who have learned to play a few licks off a bunch of Ramones and Cramps records. But no. There’s a stop cue and then the vocal comes in – “Come on, baby”…

How many rock’n’roll records start with “Come on, baby”? I mean, please… But this woman (already I don’t want to call her a girl singer) is singing it like it’s something really special. And I don’t mean that in some corny condescending way like, she makes it sound brand new. On the contrary, she sounds like she’s sung it a million times and it’s as natural to her as breathing – in other words, she sings with the ease and assurance of a real blues singer. But this woman is young! Or at least I think she’s young. And white! Or at least I think she’s white. She’s from Detroit. She fronts this band. What’s her name?

I ask Ben. Rachel. Rachel Nagy. Nagy? Nagy. OK. Apparently she’s a real character. Never sung in a band before. She was a friend, she was a butcher by trade, she was a stripper, she was a drunk, she was a handful. How it happened was one day this Detroit garage band had decided they needed a female singer, and someone suggested Rachel, the blonde who people kept tripping over when she was sleeping off a hangover. Turns out she could sing pretty good.

Damn right. I’m taking all this information in while I’m noticing that the tracks on the cd are really short and to the point, and that they sound strangely familiar – like I’ve heard them in a different form somewhere else. They only do covers, Ben tells me, by way of explanation. They like to cover really obscure soul and r’n’b tunes from the late 50s/ early 60s – stuff that hardly anybody’s heard, obscure ‘B’ sides, long forgotten album tracks etc. The way they tell it, there are too many songs in the world already, and some of the good ones never got heard by enough people so they’re just gonna play the ones they like and that they feel they can do justice to.

Impressive? That’s fantastic! Such humility! So commendable in a rock’n’roll band! Archivists, librarians, true devotees, righteous rockers. Oh God! This band is for me.

Rock’n’roll has many strains. Those of us here in its church pay many different obeisances. Some prize a good tune, others a wicked groove, a bitchin’ solo. You know… Some of us like girl group pop from the 60s – The Shangri La’s, The Ronettes, The Crystals etc. If we like them then the chances are good we like soul and r’n’b from the golden days when Motown was young and merely the biggest of hundreds of little independent labels all across the USA. But then we might also like The Ramones, and if we do, we probably have more than a little time for the great Detroit bands: The Stooges, MC5, Mitch Ryder etc. But it can be a lonely faith. Sifting for scratched up singles on the internet, bidding the housekeeping money on an original copy of Barbara George’s “I Know” on the AFO label, wondering if we can also afford that Sugar Pie DeSanto on Chess – and is the condition really vg? Or is it really tf (totally fucked)? And it can be dispiriting to continually have to face the non-comprehension of friends and contemporaries – “Why don’t you just buy the cd compilation?” – whose faith is willing but essentially weak. Thus it is that for a true believer the emergence of a band like The Detroit Cobras is almost too good to be true. Like a fantasy reward we had long given up on ever receiving.

So Ben was right. I do like them. Ben grins, and promises to send me a promo. He mentions that they are playing in New York next week. At the Bowery Ballroom. Astonishing! I’m going to be in New York next week! And I KNOW The Bowery Ballroom. I played there once.

Thus it is that the next week I catch up with my buddy in New York (who just happens to be a beautiful and glamorous blonde lady) and we go down to the Bowery Ballroom and check our names off the guest list and SASHAY inside. New York is like being in a movie anyway, but this is an especially cool episode. The Fleshtones are on first and put on such a polished show that I’m thinking that The Cobras had better be good. (Already they have become “The Cobras” since I’ve played the “Mink, Rabbit or Rat” album into the ground for the last few days.) The city of New York has just banned smoking in public places but there’s Rachel onstage with a cigarette claiming, “it’s a prop”. She’s superb. She’s perfect. The sound is lousy and the performance a bit sloppy but The Cobras have so much rock’n’roll righteousness going for them that they can actually afford to be a bit sloppy. But… This is a dangerous game. It’s dangerous to allow nonchalance to become sloppiness because it can lead to contempt for the audience, which is contempt for oneself. And that’s unacceptable. Also, in the market place nowadays, it’s clear that there is no room for sloppiness of any kind. In that sense, The Cobras were nowhere near slick enough. But fuck that. The Cobras aren’t slick; they’re a real rock’n’roll band just like the old days. I’m 43 and they made me feel 19. Somehow, and I cannot understand how, they are not an anachronism, they are not IRONIC, they’re not being deliberately RETRO… Thank God. Something real, and tough, and true, and hip, and funny, and stylish, that ROCKS!

Yes, it was more than wonderful to see The Detroit Cobras in New York in April of 2003. It was love. For the first time in many years, I was in love with a band that was still actually functioning.

I downloaded as many tracks as I could find on the Internet and was overjoyed when Rough Trade here in London got a few vinyl import copies of their two albums. Ben had sent me the new 7 track ep out on Rough Trade, “Seven Easy Pieces”, that began with Rachel saying “very nice!” in the sexiest and most sardonic manner imaginable – before launching into an epic rock’n’roll stomp called “Ya Ya Ya (Looking For My Baby)” with Rachel plaintively singing how she’s “looking for my baby but my baby ain’t nowhere around”. Still, when she finds him she’s going to “take him by the balls and drag him all the way back to town”, so it’s probably wise not to feel too sorry for her. Yes, like so many guys, I love a ball-breaker. Rachel’s the best, and toughest sounding rock’n’roll singer in the world right now. There’s no-one in her league.

So how can The Detroit Cobras exist? How can they get every detail so right and STILL be contemporary? How can their records sound so good and STILL be modern? How do they KNOW? They’ve been criticized (by fools!) for not doing any original songs. Any idiot can write songs. All you need is a guitar and three chords. What The Detroit Cobras do is so much more interesting: The trick for them is to unearth a forgotten gem – a song that only a true devotee would know. They’ll take, say, an early 60s ‘B’ side by Irma Thomas (that’s NEVER been anthologized on cd!) and boil the brass and piano parts down to two sprightly guitars, maybe simplify the bass line and bring it forward a little bit, possibly up the tempo just a tad, you know, as a nod towards the punk aesthetic, and they keep the song short, specific and to the point, absolutely no padding with indulgent solos. And then, out in front, Rachel makes every song her own.

Unless you’ve heard them, I can’t convince you. You’ll just think I’m bigging up a band I like and in a way that’s true. How could I not love The Detroit Cobras? They validate everything I believe about good rock’n’roll: short sexy songs, tightly played, with ingeniously unfussy arrangements. In interviews, The Cobras reveal themselves to be such high-minded purists that they would probably hate the comparison, but the nuts and bolts of what they do is virtually identical to what The Beatles once did to things like Smokey Robinson’s “You Really Got A Hold On Me”, Barrett Strong’s “Money”, or The Shirelles “Baby It’s You”. It amounts to taking what may be quite exotic and polished arrangements by trained professional musicians and re-casting them for souped-up electric guitars and drums. If that sounds easy, you should try it sometime. Besides, when The Beatles were doing it in the early 60s, they had an unplundered sackful of classic songs to choose from that were virtually unknown to their audience. Fast-forward forty years and all of those hit songs are in the public sub-conscious, memorized from any number of compilations, played by a million bar bands across the years. The Cobras could be the greatest bar band in the world if they wanted to be; it’s their attitude and choice of material that marks them out. It has to be impeccable, and it is. Only true believers could find and lovingly tease such obscure tucked-away ‘B’ side gems into such vibrant, breathing life. They record for a label called Sympathy For The Record Industry and their albums are 13 or 14 tracks long and still clock in at less than 32 minutes. Rip-off, you say. You’re wrong. 13 or 14 songs in 32 minutes mean no padding, no waffling, no bullshit. All the songs have memorable tunes and good lyrics and strong grooves. They don’t sound alike in the way that The Ramones (bless them) sounded alike. There are fast songs and slow songs; in amongst the soul and r’n’b there are blues and country songs, surf, pop, even the occasional waltz! The cd’s are also pressed in vinyl editions with no barcode on the covers. Think about that for a moment. No bar code. Think about the implications of that in the modern retail industry. Their graphics are mildly pornographic: featuring Rachel with an expression like “Oh yeah?” on her face.

It’s hard to get concrete information. The first album “Mink, Rat Or Rabbit” came out in 1998. The second one, “Love, Life and Leaving” came out in 2001. The 7 track ep, “Seven Easy Pieces”, came out in 2003. They’ve recorded some tracks for compilation albums in Detroit; they’ve put out the odd limited pressing single. Who’s in, who’s out of the band, seems to fluctuate, there’s quite a floating line-up. The only real constants are Rachel and Maribel Restrepo on guitar. I’ve been putting off writing this piece for too long because of a lack of biographical information, but the hell with it, it’s a gush and a labour of love. I’m sorry. But it’s personal. When “Cha Cha Twist” (the first track on the first album – the one that starts with “Come On Baby”) got used in a Coke-Cola advert on TV my first reaction was outrage: How DARE they? The Detroit Cobras are MINE! These yuppie fucks don’t get the importance of the Cobras; they’re just USING them to sell a product. Then I realized I was being, uh, irrational. It was GOOD that they were making some money, that they were getting some exposure. Wasn’t it? I worried about the band, and Rachel in particular. Some months ago, Rough Trade had put out a sampler of a bunch of their acts covering each other’s songs. The Cobras had done The Strokes “Last Nite”. Of course, this was not the kind of song they would normally cover and where the original was a foursquare rip-off of Iggy Pop’s “Lust For Life”, the Cobras version lent it a rock’n’roll mambo feel. But Rachel’s vocal, pitched low, gave the song pathos that Julian Casablancas could only dream about. The trouble was it sounded so beaten, so world weary, so sad. Really, just so sad. It would break your heart. I was hoping this was method acting but worried that it wasn’t. I’d heard dark rumours of bad things happening on the road. Oh God that would be just too painfully fitting: Isn’t that exactly what happened to Detroit’s last great rock’n’roll singer, the aforementioned Mr. Pop? When The Stooges were far and away the greatest rock’n’roll band on the planet, what did they do? Got hooked on junk and threw it all away.

Anyway, enough of this maudlin speculation. It’s 4:10am and the last I heard was The Detroit Cobras were in LA working with Jackie DeShannon, who wrote at least one of the tunes on their albums. Next up they’re gigging around the West Coast and if any of you lucky Americans get to read this in time, I suggest you go and see them. I hope they achieve great success, and that they can handle it when it comes, and that they go on to make many more magnificent records; but even if they split this very day, the records they’ve made will last as long as good rock’n’roll is listened to.

And Rachel, if you’re reading: Thank you for singing like that.

-

Tryin’ To Get To Elvis

In the library today I put on the Sun Sessions to cheer me up while I was working. When it came around to the bridge of “Tryin’ To Get To You” I found myself spontaneously weeping. Curious. I couldn’t think of any concrete reason for this. I had already become quite emotional during “Milkcow Blues Boogie” – specifically the point where he sings:

“In the evenin’, don’t that sun look good goin’ down

But don’t that ol’ moon look lonesome when your baby’s not around”

But that’s the beauty of the poetry of the blues. Isn’t it?

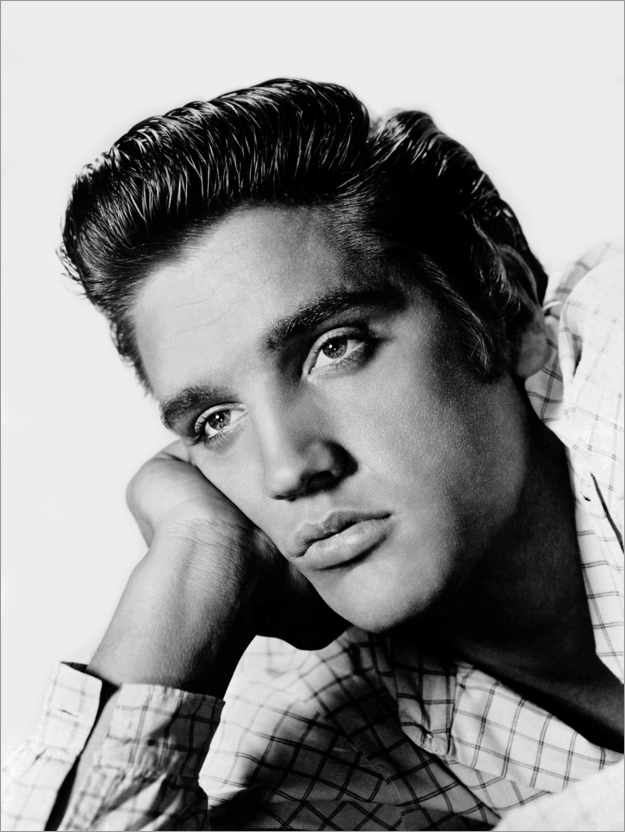

I thought about Elvis. How enigmatic a figure he really was, and is. How long after his death his power remains completely undiminished. How, if anything, it has increased and codified. There are places in the South where he is prayed to as a saint. But what does that prayer represent?

There’s something about him, something that has never been fathomed, even now. So many people have written about him, so much verbiage. Yet the secret is untouched. One can point out how innovatory he was in terms of race – a white man on his first record singing black music as white music, and then, on the other side, singing white music as black music – and certainly it’s true that he was completely unique in this respect. But there’s something else. The existence of this something is universally acknowledged by those interested in pop culture and it’s history, but nobody has ever got to the bottom of what it really is. It’s a fact that first editions of the Sun singles (there were only five of them) are among the most prized collector’s items, regularly selling at auction for upwards of three to five thousand dollars each – even in less than mint condition. And it’s a fact that they apparently meant little or nothing to Elvis himself: one felt he regarded them as slightly embarrassing. In an interview clip I saw from ’69 where a journalist asks him about the Sun sessions Elvis’s only response is: “They sure got a lotta echo”. Yet, seemingly completely effortlessly, Elvis, Scotty Moore and Bill Black created a sound that resonates just as perfectly and mysteriously now as it did the day they made it. The perfection part is easy to nail: perfect recordings perfectly capturing perfect performances. But the mysterious aspect continues to elude explanation. The recipe for the atmosphere on those records is so superficially easy to conjure: three Southern musicians – two of them seasoned professionals, one, the singer, a fresh new talent – having a good time “goosing up” some country standards and some black r’n’b. The music is wonderful, fresh, vibrant etc. But that’s not it. What is it about those records that is so unique? It’s something to do with America. Some sort of genuine truth about America. I’m sure it is. But what is that?

If you don’t care about America, if Americana has no allure, chances are you don’t like Elvis anyway. But if, like me, you’re hooked on America, then there’s something in these records that tells you something about the place. Something that you need to know, that will predicate your conception of what America really is. Truths about America are everywhere, good and bad. But what kind of truth is this? A truth that actually tells you nothing but suggests a secret, a secret that contains the key to something of fundamental importance, that you knew but had somehow forgotten.

In cultural terms, it MUST be something really quite substantial when you consider that these records provided the foundation stone for the career of a man who brought about a complete revolution in the attitudes and behaviour of vast numbers of people in the Western world – without even thinking about it, without even being aware of having done it. On some very real levels, Elvis changed everything. And this revolution continues to reverberate, as if Elvis rang some deep primordial bell that, once sounded, just gets louder and louder forever, or until the civilisation finishes.

In 1977, in his obituary of Elvis, Lester Bangs wrote: “Elvis replaced ‘How Much Is That Doggie In the Window’ with ‘Let’s fuck’, and the world is still reeling from the implications of that”. What Lester couldn’t have known, dying as he did himself a mere five years after Elvis, is how completely Elvis’s power would remain undiminished, untouched. “Worship is a habit that’s hard to break”, wrote Nik Cohn of Elvis as far back as 1969. How completely he was right. Only the other day I heard on the radio an interview with a president of one of Elvis’s fan clubs in the UK, and the man was positively incandescent with worship.

Maybe it is just that animalistic call to carnal action that will always resonate with human beings under any circumstances. But isn’t it more than sex, isn’t it freedom as well? When Elvis sings that line I quoted earlier:

“In the evening, don’t that sun look good goin’ down”

there is something in his 19 year old voice that offers to the Southern sunset a distillation of yearning. It’s like a wish. A real wish. What is he wishing for? This young man made of the clay of rural America? Whatever it is, it’s something to do with the deepest dreams and wishes of America itself.

Elvis made far more crappy records in his (relatively) brief career than good ones. Even mediocre ones shine like beacons throughout his post Sun discography. As early as 1957 he was already parodying himself on songs like “Teddy Bear”. Any fan will tell you of his “good” periods: but what that actually translates to are periods when he made fewer bad records than at other times. Yes, there are a few classics in there – “Suspicious Minds”, “Guitar Man” to name but two – but compared to the Sun sessions? Only “Stranger In My Own Home Town”, from the “In Memphis” album – where Elvis sings the title line over and over again into the long fade-out – THAT has the same air of mystery about it. But there it’s as if he is desperately searching for something he has lost. And what of the bad records? The terrible soundtrack albums, the abominable ballads from the dregs of Tin Pan Alley where Elvis sings like a man in a stupor of indifference. How could he have gone from such great artistic heights to such appalling depths of schlock without even seeming to notice?

There’s a clip I’ve seen of Elvis’s first Hollywood audition. He is handed a guitar with no strings on, just a prop. He looks at it in amazement before taking it and miming to “Blue Suede Shoes”. He does a fine job because he was always a professional but I wonder what he was thinking when he saw that the guitar had no strings. I mean, Elvis was never a great guitar player but subtract his contribution from the Sun sessions and they would fall apart. He played a vital role, he played it honestly and as well as he knew how. Following his success, that was taken away from him. He was made to feel that it wasn’t even remotely important. How that must have negated all those evenings spent alone in his bedroom in Memphis, strumming along to his favourite songs. All those Arthur Crudup songs, all that Hank Williams, and Wynonie Harris, and Junior Parker. Remember, in the 1968 TV special, how happy he looked to be actually playing the guitar again? Not miming, but really playing on a big old Gibson with a fat sound? In the prosaic terms of a career in showbusiness, Elvis had obviously only wanted to be a movie star. Singing came too easily for him to really have that much respect for it. But playing that Jimmy Reed song (“Baby What You Want Me To Do?”) over and over, as he did, playing the same turnaround at the end of every chorus with the delighted look of a child who has re-discovered a much loved toy that had been lost. Doesn’t he look great? Doesn’t your heart go out to him? Suppose Elvis had never met the Colonel, had never achieved much more than local success: the whole fabric of Western culture would have been different but, perhaps, Elvis Presley would still be alive.

Reading the biographies, it’s astounding that he lasted as long as he did. He punished his body so terribly. How valiantly his spirit must have fought against the abominable regimen of junk food and hideous chemicals its desperate owner forced it through. Talk about a soul in torment! Elvis gave his life. He really did. He was a king in a republic with no history or culture of kings. So when you listen to that music, that music that he made as a 19 year old truck driver from Memphis; then as a young god of 20, 21, don’t forget to genuflect a little. And then get “real, real gone for a change”. Because it’ll never, ever, ever be that way again.

-

Gentleman Joe Strummer

Written when I heard the news of Joe Strummer’s tragically early death.

——

Back in the winter of 1975, when I was 15, I went with my sister and a friend to see Roger Ruskin Spear – the ex-Bonzo Dog – put on his Kinetic Wardrobe show at Hampstead Town Hall. The supporting act was a rough and ready rock’n’roll band called the 101’ers. I remember being excited and impressed when the singer and guitarist launched into a blistering version of The Beatles’ ‘Back In The USSR’. Little did I know I was watching Joe Strummer. He was just a bloke with curly hair yelling at the microphone and bashing hell out of a Fender Telecaster. I looked at him and I knew I liked him. He was alright.

Within a year of course, punk rock had exploded and Joe Strummer was fronting a new band called The Clash who played all their own material: songs with titles like ‘White Riot’ and ‘I’m So Bored With The USA’. Having seen him with The 101’ers bought me some playground kudos amongst those of my schoolmates who actually believed me. Among these was a boy called Guy who was good at art and who was the first at my school to adopt the punk look and attitude. We became friends and he would bring round things like The Sex Pistols ‘Spunk’ bootleg and The Clash’s ‘Capital Radio’ interview ep for me to tape. Armed with Mark P’s magnificent dictum: “Here is a chord, here is another, here is a third, now go form a band”, I had become reasonably adept on guitar, and on Christmas Day 1977, Guy came round unannounced (nobody comes round unannounced on Christmas Day) and asked me to teach him. I showed him how to play the intro to ‘Pretty Vacant’ and he walked off back to Earl’s Court happy as a lark.

Before this, though, the Clash’s first album had come out and I had bought it and played it loud and often and taken it to parties and annoyed people with it who would rather have been getting off to Genesis and Peter Frampton. I didn’t like the second album, toe-ing, sheep-like, to the then- fashionable line that The Clash had somehow sold out by allowing it to be produced by an American mainstream producer. But the third album, ‘London Calling’, was the goods and no mistake – ‘Exile On Main Street’ for my generation, the best album made by any of the British punk bands of the late 70s. By the time it came out, Christmas 1979, I had become what you might laughingly call a professional musician, and I remember hearing the title track for the first time in a Paris nightclub where I was playing with my first ‘proper’ band, The Cannibals. I was 19 and I was dancing with a pretty girl and there was Joe Strummer’s voice singing “London Calling”. I’m all grown up now and I am extremely wary of overly romanticising rock’n’roll (for good reason) but I can’t deny that THAT, that is a very fond memory indeed.

Fast forward more than 20 years to the summer of 2002 and I get a call from a friend of a friend, a colleague of a colleague, the sitar player from Cornershop. She’s double-booked herself and she’s heard that I play sitar. Could I dep for her on a few festival gigs with Cornershop?

“How long have I got to practice?” I say.

“Three weeks”, she replies.

“What’s the money?”

“Crap”.

OK. The first gig is in front of 45,000 bozo Oasis fans at Finsbury Park. They chuck plastic bottles but they’re so far away they can’t reach me. So far, so good. The last of the gigs is a festival in Cardiff. The only time available for soundcheck is first thing in the morning so we’re travelling the night before in a sleeper tourbus. The meet is outside the rehearsal studio at 10pm. So I turn up on time outside The Depot in Brewery Road with my two sitars in their monstrous cases and there’s the tourbus. It’s locked so I knock on the driver’s window to get him to open up the equipment trailer so I can load my sitars and get on board, grab a decent bunk. As I’m putting the sitars in I notice that none of the equipment looks at all familiar. With a hesitant air I ask the driver:

“This is Cornershop’s bus, isn’t it?”

“Oh no, mate”, he replies, “this is Joe Strummer and the Mescaleros!” Close! I haul the babies off the trailer and wander down the road where I can see another tourbus. I knock on the door.

“Is this Cornershop’s bus?”

“No mate, this is Alabama 3. Where are you headed?”

“Cardiff”, I reply.

“Oh we’re doing that gig. You can come with us.”

I make my excuses: “Thanks but I better wait for the right bus. I don’t want to piss off the tour manager.”

“OK. See you there!”

“Cheers”.

I wander back towards the Depot. As I’m standing on the street, looking forlorn with two sitar cases in tow, who should emerge from the building but Joe Strummer himself. He smiles broadly. He walks over to where I’m standing. He speaks.

“Alright? How ya doing?”

I smile back. I’m feeling a bit nervous. I’ve met lots of famous people and I don’t get nervous – but now I’m feeling a bit nervous. This man was so much a part of my youth, so much a part of everything I ever aspired to join in with. I explain my situation: why I’m standing on the street with two sitars in big cases, how I don’t do mobile phones (“Neither do I”, he chuckles) and where is the Cornershop tourbus? He listens attentively. He deliberates. Then he says, “Tell you what. Put your sitars on my bus and we’ll go down the pub and you can use my guitarist’s mobile to phone your tour manager, find out what’s going on.”

Wow.

“OK,” I agree, feeling not quite unlike a fool. I pick up the cases but Joe Strummer says, “Here y’are”, and takes one of them off me and carries it over to the door of his bus. He unlocks the door and puts the case inside and I put the other one inside. He locks the door. We walk down the deserted road together. He has just finished rehearsals for his tour and is about to embark upon it. He is relaxed and amiable. I am overawed and uptight and worried. I ask him if he still lives in West London but it turns out that he has lived in Somerset for several years now.

“I thought I hadn’t seen you on the streets for awhile”, I say, and don’t like the way it comes out. But it’s true! I used to see him around Notting Hill and Portobello on a regular basis and it was always nice to know that Joe was still in the neighbourhood. I tell him how the area is being turned into a yuppie theme-park, how he wouldn’t recognize the end of Westbourne Grove, how the Blue Sky café has been closed down. I realise I’m whingeing but he looks sympathetic. We arrive at the pub and Joe introduces me to all the members of his band who are standing outside the bar, merry and getting merrier. He commandeers the guitar player’s mobile phone.

“You call your tour manager and I’ll get you a drink. What you drinking?”

“Um, OK. A pint of bitter please.” Joe Strummer goes inside and leans on the bar with a tenner in his hand. I am instructed in how to use the mobile phone and I call the tour manager. I have gone to the wrong studio! I should be at Terminal which is by London Bridge! Miles and miles away!

“Don’t worry”, says Yaron the unflappable tour manager, “get in a cab. We won’t go without you.”

I hand back the phone to its owner. Now I really feel like a fool. And here’s Joe Strummer with a pint for me.

“Thanks Joe”, I say. I need a cigarette. I produce my packet of Cutter’s Choice tobacco. Joe produces HIS packet of Cutter’s Choice tobacco and clinks mine with it. Hey, I smoke the same cigarettes as Joe Strummer, says the16 year old in my head. Meanwhile the 42 year old nincompoop that I have become explains the situation. But how am I going to find a cab? This whole area is virtually an industrial estate.

“I’ll get the barman to call you one”, says Joe. He hands me a key. “You better go back and get your sitars off the bus. Don’t forget to lock it up after you. I’ll watch your pint.” He takes it off me and he goes back into the bar to get me a cab. I trot back up the road to the bus, get the sitars, lock up carefully. When I get back to the pub Joe has my pint carefully lodged behind him. I retrieve it gratefully. Everyone is chuckling at my predicament. Hapless is the word I’d use. But the cab arrives before the conversation dies. I down the rest of my pint, feeling embarrassed that I won’t get to buy him one back. As the band look on Joe carries one of my sitars to the cab while I carry the other one.

“Thanks, Joe”, I say sheepishly. “Thanks for everything. You’re a gentleman.“

And I wish there was some way to convey to him just HOW much of a gentleman I think he is. As I clamber in he says:

“Say hello to Tjinder from the Mescaleros. Don’t forget to give it some …” He gestures with his arm and clenched fist to indicate strength and commitment and I’m off. I look back out the window and Joe Strummer is waving goodbye to me.

And now I learn that that hale and hearty man, that true gentleman of the road, of rock’n’roll, is dead. At 50, of a suspected heart attack, three days before Christmas. What a shitty Christmas present for his wife and two kids. What a shitty Christmas present for all of us. For we are all impoverished by Joe Strummer’s death. Whether we give a flying stuff for The Clash, or the Mescaleros, or rock’n’roll at all, we are all impoverished by the loss of a great big-hearted man who believed in what he did and who did it for all the right reasons. Talented, genuine, truthful, he was unique. The music business is full of petty little people. Joe Strummer was not one of them. He was an old-school rock’n’roller, someone who cared. God bless him.

-