Once upon a time Richard Branson wasn’t a bad joke but the proprietor of a few record shops and a maverick indie record label. He was never particularly interested in music but he was savvy enough to employ people who were. After catching one of the luckiest breaks in the history of the music business with Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” – who could have guessed that hundreds of thousands of people would want to buy 50 minutes of hippie muzak? – Branson’s A&R department assembled a roster of uniquely interesting artists. Very much like Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, Virgin Records in the early to mid 70s was a trademark of quality. If it was on Virgin you might not like it but it almost certainly wasn’t boring. In 1973, Virgin put out “The Faust Tapes” for the price of a single – 49p. Like thousands of others, I was intrigued by the Bridget Riley cover (“Crest”) and enticed by the low price. I would have been nearly 13 years old. I bought it and took it home and played it on my long suffering parents teak stereogram. Well… The Beatles “White Album” was the second album I ever owned and I was one of those Beatle fans who actually liked “Revolution No 9”. “The Faust Tapes” seemed like a whole album of “Revolution No 9” with bittersweet musical interludes ranging from delicate acoustic guitar set to poetry in French and German to hard rocking saxophone and electric guitar bashing. I liked it. It was ear opening stuff. Thanks Richard. Nice one.

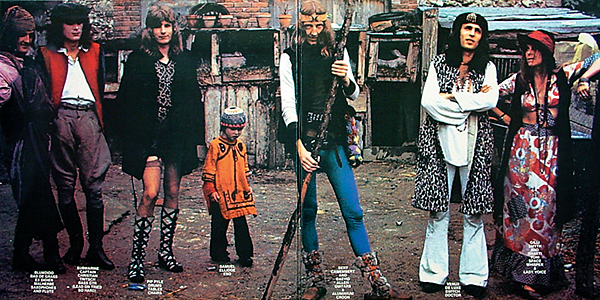

The following year Virgin put out “Camembert Electrique” by Gong, again for the price of a single which by now had gone up to 59p. I knew nothing about Gong but the cover looked interesting and, after my Faust experience, I was happy to take a punt on it. Once again, I liked it. In places it was as wacky as Faust but it was coming from a more recognisable place. Or so I thought. There were electric guitars and drums and bass. Some of the tracks seemed to be actual songs. You know. It sounded a bit like rock music, or thereabouts. I loved the “space whisper” of Gilly Smyth. “I am not free… I am not free…” It got right inside my head. It didn’t sound like anything else. Once again, thanks Richard. (Oh I know, it was probably Simon Draper, but Branson paid for it.)

In the Punk purges of ’77 and ’78, like a lot of pretentious posers of my generation, I got rid of large chunks of my record collection in case I was seen in possession of a Deep Purple or (worse) a Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow album. A lot of deadwood was disposed of but also a lot of babies were thrown out with the bathwater. I had to buy back all my Free albums over the next twenty years, for example. That’s fashion. But funnily enough, “Camembert Electrique” never got culled. It would sit there, in my collection, unplayed but strangely immune to purges, for year upon year. I remembered that I liked it and that was enough.

So the other day, for no particular reason, I played it. How does it stand up? Strange record. What is the vocabulary of this music? Does anyone care any more? In the intervening 45 years or so I had learned all the back story: Gong were formed in France by Australian Daevid Allen who had been forced to leave Soft Machine when he was refused re-entry into Britain after having overstayed his visa. Allen and his wife Gilly Smyth were old style/ new style bohemians, propagandists for what became the hippie lifestyle. Allen wasn’t much of a musician but he was an effective bandleader and he had a vision. He had the talent for drawing musicians in – excellent players like Didier Malherbe and Steve Hillage – and bending them to his will. Later on, he would develop that irritating twang that suggested that if only everyone were as hip and knowledgeable as he, then how much better the world would be (Roy Harper and Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson are also guilty in this regard). But “Camembert Electrique” doesn’t suffer from that insufferable Flying Teapot/ Pothead Pixie mythology that would overwhelm Gong albums until they sounded like membership cards for an idiot club. Instead, you get a bit of tape collage, a bit of random dialogue, leading into a six minute song called “You Can’t Kill Me” made up of whole tone scale riffs and odd time changes and lyrics full of angry paranoia. It’s quite full on. Gong weren’t at this time possessed of the chops to play the jazz/rock fusion that would bore them and their audience into somnambulent submission at the end of the 70s. Here they trundle along, pulling these angular riffs behind them with all their strength. It ends abruptly and then begins… a joke track. A silly mock-portentous song in praise of being stoned. Well, is it really so much more risible than “Drinking Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee”? A lot less danceable certainly. But these two tracks set the tone. Allen really liked the whole tone scale. It provides the basis for a lot of this music. But the whole tone scale doesn’t really go anywhere (except, perhaps, to the nut house) and it’s when you get a bit of relief, as in the gentle melody of “And You Tried So Hard”, that the album’s enduring likability returns into focus. In 1971, when the album was recorded, Gong were unequivocally a hippie band. They lived communally and no doubt took industrial quantities of psychedelic drugs. Out of this came music which was unique to them. Those who love it love it fiercely. Gong never sold out but they changed, inevitably they became more professional and eventually the musos took over and Allen found himself cutting out of his own band. Some people like the jazz/fusion Gong. I’m not one of them. I don’t even much like jazz/fusion when it’s done properly. But I find I still like “Camembert Electrique”. Its a brave little record, a friendly record but with teeth – when Gilly Smyth intones “I Am Your Animal” she’s not messing about. There’s nothing else like it and anyone who is interested in what happened to that little corner of the psychedelic past should find it, or dig it out, and dust it down and listen to it.